Facebook helps motivate the next generation of hackers

SAN JOSE, Calif.—With fluorescent lights overhead and student projects hanging on the walls, Kathy Smith’s classroom at the Daniel Lairon College Preparatory Academy, a middle school 27 miles down Highway 101 from Facebook’s headquarters, looks like it could be at any one of the more than 66,000 public elementary and middle schools across the United States.

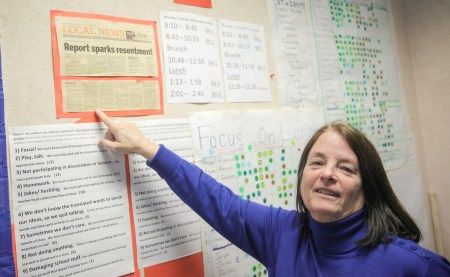

Two things stand out: First, it is hard to distinguish Smith’s desk from her students’, as it is bunched in a crowded array of desks with theirs. And second, an article from the San Jose Mercury News newspaper about Lairon Academy and other public schools in the area, framed in bright-orange construction paper, hangs on the wall.

Smith, who in November 2014 cut out and highlighted in yellow several parts of the Mercury News story, points to the sentence that stands out to her most: “More than 15,000 students attend chronically underperforming schools that steer them toward failure and a lifetime of low wages,” the 62-year-old lifelong teacher reads aloud, jabbing her finger at the clipping.

“We do not ‘steer them’ toward failure!” she corrects. “Just because they come from lower-income backgrounds doesn’t mean they’ll stay there,” she says. “And not having a ton of money doesn’t mean you can’t go to college.”

RELATED STORY: How to choose a hacking camp for kids

Since framing the article, Smith has translated her anger about its characterization of her English students’ potential into motivation to help them succeed.

Determined to give them a leg up in technology, she convinced several Lairon students to participate in the CyberGirlz program at San Jose State University, which focuses on teaching middle-school girls about computers and cybersecurity. Then, through connections she made at CyberGirlz, she convinced Facebook to sponsor her computer science class in the Air Force Association’s nationwide “young hacker Olympics,” known as the CyberPatriot program, and she started teaching a class based on the program. She split her class of 30—24 girls and 6 boys—into six teams of five students each.

“We’re trying hire them,” said Facebook security engineer Teddy Reed, a mentor to Smith’s class. “Several of the girls can already kick our ass.”

Kathy Smith, who teaches Daniel Lairon Academy’s computer science class, points to the news story about her school that inspired her to get the students to sign up for the CyberPatriot competition. Photo by Seth Rosenblatt/The Parallax

CyberPatriot, which runs the largest “capture the flag”-style hacker game in the world—with 3,379 teams, each participating for six hours straight—is designed to teach middle-school students the basics of hacking and computer security. Teams compete to be the fastest and most accurate at completing a series of hacking tasks related to subjects they study in the classroom, from revoking account privileges and creating strong passwords, to finding and removing malicious software such as keyloggers and rootkits.

Smith’s teams are the first sponsored by a Silicon Valley technology giant. They are the first in the eight years of the CyberPatriot competition, in fact, to register from all of Silicon Valley.

Why is the program focused on middle schoolers, as opposed to high schoolers? Facebook’s Reed says the Air Force Association, a nonprofit based in Arlington, Va., found that kids in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades tend to be more open than older kids to taking on new challenges.

“Before kids have found their passion,” Reed says, the organization and its corporate mentors have the opportunity to draw them in. To the students, “we can say, ‘Here’s this super-challenging but super-rewarding thing you could love.” Reed and his co-mentors help the students learn the basics of computer security. That includes technical knowledge, such as how to secure a Linux computer, what cryptography is and what it does, and what it means to visit a website with a secure connection. It also includes relevant history, such as who the first computer programmer was. (Hint: It wasn’t Al Gore.)

Michael McGrew, another Facebook engineer who’s mentoring the team, emphasized that the skills the students are learning form the foundations of modern computer security. “Many kids have used a Windows computer or Mac,” he says. “But when you look at what runs the Internet, it’s a lot of Linux servers. Later on, when they’re learning about Linux, they won’t have to learn the basics.”

“Just because [the students] come from lower-income backgrounds doesn’t mean they’ll stay there.” — Kathy Smith, teacher, Daniel Lairon College Preparatory Academy

One of Smith’s six teams made it to the CyberPatriot semifinals, held February 19 to 21. Nobody on the semifinalist team of four girls and one boy expressed an interest in pursuing a career in computer security—or even at Facebook. All five of them, however, said it is important to know how to protect yourself and others when using computers.

Daniela, a 14-year-old who wants to become an immigration attorney, says it will be important for her to protect her clients’ information. Her team finished 10th out of 103 California teams, and 50th out of 480 teams nationwide.

“Not bad for a group of kids who come from a school where 96 percent of the students are on free or supported lunches,” Smith says.