Can your vote be hacked—after you cast it?

In early August, Donald Trump began expressing fear that the U.S. presidential election would be “rigged” against him.

“I’m afraid the election is going to be rigged, I have to be honest,” Trump told an audience in Columbus, Ohio.

While much has been written about his remarks—as well as several others he made in the weeks following the Democratic National Convention—it remains an open question whether electronic databases storing votes can be hacked and manipulated.

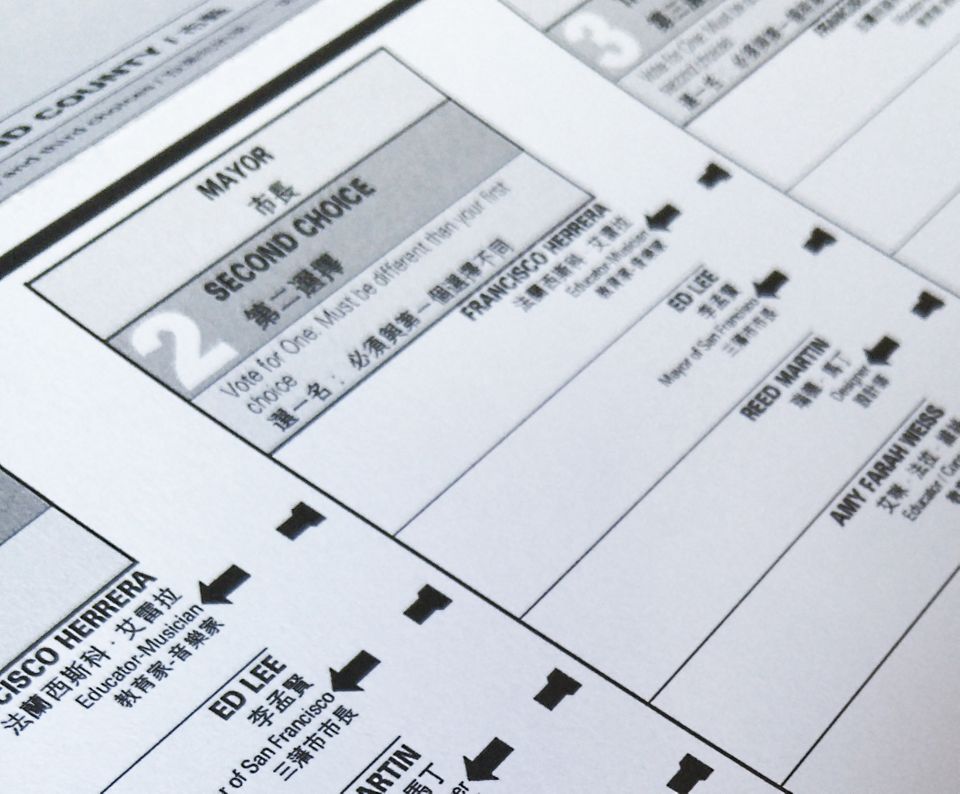

Voting has entered the digital era on two fronts. Electronic voting machines and, in some locations, Internet voting have introduced numerous opportunities for hackers to alter voting records. It is the security of massive spreadsheets recording the will of the people that concerns Richard Forno, a computer security expert who recently thrust himself into the national debate over the hackability of U.S. elections by publishing a column on the subject.

“Everyone’s focusing on the edges of the network, the voting machines, but no one’s looking at the databases,” Forno, a career computer security expert and currently the director of the Graduate Cybersecurity Program at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County, tells The Parallax.

The decentralized nature of U.S. elections, which are run by local municipalities and protected by the states’ rights provisions of the Constitution, has long precluded the setting of national computer security standards to protect the databases that tabulate and store votes.

“There’s no surefire way to prevent hacking,” he says, “but if you’ve got good auditing procedures in place, you can catch any tampering.” — Chris Jerdonek, vice president, San Francisco Elections Commission

In response to the punch card system failures that led to the “hanging chad” debacle of the 2000 presidential election, the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002 provided states with financial assistance to modernize their voting procedures. It included a funded mandate to states to create a voter database, but it let each state decide whether to include voter data beyond names.

Since then, voter registration databases have been hacked with alarming regularity, from those of Illinois and Arizona to one that had culled voter data from the entire nation. Although much of the information contained within these databases was already publicly available, the hacks raised questions about the security of databases used to store voter registrations and voting records, Forno says.

“A database where all the voting results are uploaded is an interesting target,” he says. “Can hackers create a situation on these voter authentication systems where they’re undermining the trust in the system?”

Database security expert Ben Caudill, founder and CEO of Seattle-based Rhino Security, says he wouldn’t be surprised by news of a successful hack against a local government agency that tabulates votes.

“Local governments tend have some of the worst security I’ve ever seen,” he says. They often have “lots of missing patches, poor training on the part of security administrators, and outdated software.” Information technology, he adds, “is not a priority.”

Election departments contacted for this story, including those in California and Illinois, did not return requests for comment. However, Chris Jerdonek, a software developer who serves as vice president of the Elections Commission in San Francisco, a seven-member board of appointees who oversee the city’s elections, says transparency would help detect election database hacking.

“There’s no surefire way to prevent hacking,” he says, “but if you’ve got good auditing procedures in place, you can catch any tampering.”

Pamela Smith, president of Verified Voting, a nongovernmental organization that works on ensuring election “accuracy, integrity, and verifiability,” says her organization recommends disconnecting from the Internet the computer on which election databases (used to tally up voting precinct data) are stored, a practice known as air-gapping because the computer is separated from the Internet by an air buffer.

“If someone could get access to that central tabulator, that could be problematic,” she says.

An interactive map produced by Verified Voting shows how U.S. voting precincts have implemented electronic voting. According to the map, five states—Georgia, Delaware, Louisiana, New Jersey, and South Carolina—do not require a paper trail to accompany their electronic voting records. Were vote tabulation databases to be tampered with in those states, Smith says, it would be impossible to reconstruct voters’ intent.

How to protect voter databases

A properly protected vote database is not easy to hack.

“It would have to be done as an inside job,” Forno says. “I doubt you’ll have someone in a college room in Eastern Europe hacking a voter registration system.”

Caudill speculated that to alter a vote database, a hacker would first have to phish its log-in credentials from a computer system administrator, software engineer, or elections department official. In theory, he says, those databases should be heavily protected and not accessible from the public Internet or even the internal elections department network.

“Because this is a very sensitive database, you only want to have the log-in from one IP address,” he says. That would make it tougher to alter votes, as would encrypting specific columns of information in the database, such as voting records.

Other techniques they recommended to protect voting databases include using up-to-date antivirus software, monitoring traffic on the network firewall, separating duties and access among administrators, and hashing department passwords (using encryption to create a unique password-based fingerprint that Caudill says is “extremely difficult” to decrypt).

The bipartisan U.S. Elections Assistance Commission, a federal agency created by HAVA to offer states guidance for election procedures, as well as voting-machine testing and certification, recommends 10 ways for elections departments to secure their voter registration and vote tabulation databases.

The EAC’s recommendations include restricting database access so that authorized personnel can access only the data their job requires them to use; auditing, which ensures that the database logs user modifications; detecting attacks with a system designed to monitor the network and detect intrusions; backing up the database; suppressing data so that only necessary information is shared with outside sources; encrypting the database, its backups, and all data transmission; using firewalls to stop and report unauthorized access; mandating the use of a virtual private network to remotely access data; disconnecting the databases from the Internet and election department intranet (air-gapping); and documenting when new information is added to or shared from the database.

“In Ohio,” says Matt Masterson, commissioner of the EAC, “our protocol is to take a flash memory drive, export the results to the drive, walk them across the room, and upload them. At that point, that flash drive can’t be reused…In New Jersey, they burn those results onto a CD or DVD.”

At the end of Election Day, Caudill says, protecting voting databases comes down to basic computer security.

“We’re speculating less on defense and more on the incentive of the attackers,” he says. It’s always easier for hackers to succeed, he adds, “because they only need to find one flaw to escalate privileges and access data. The defender needs to protect against all of that.”