As bug bounties proliferate, hacking contests maintain a strong pull

VANCOUVER—Competitive hackers hadn’t even made it to lunch on the first day of the annual Pwn2Own hacking contest here last Wednesday before two contest novices used newly discovered vulnerabilities to hack Apple’s Safari Web browser for Macs and Mac OS X.

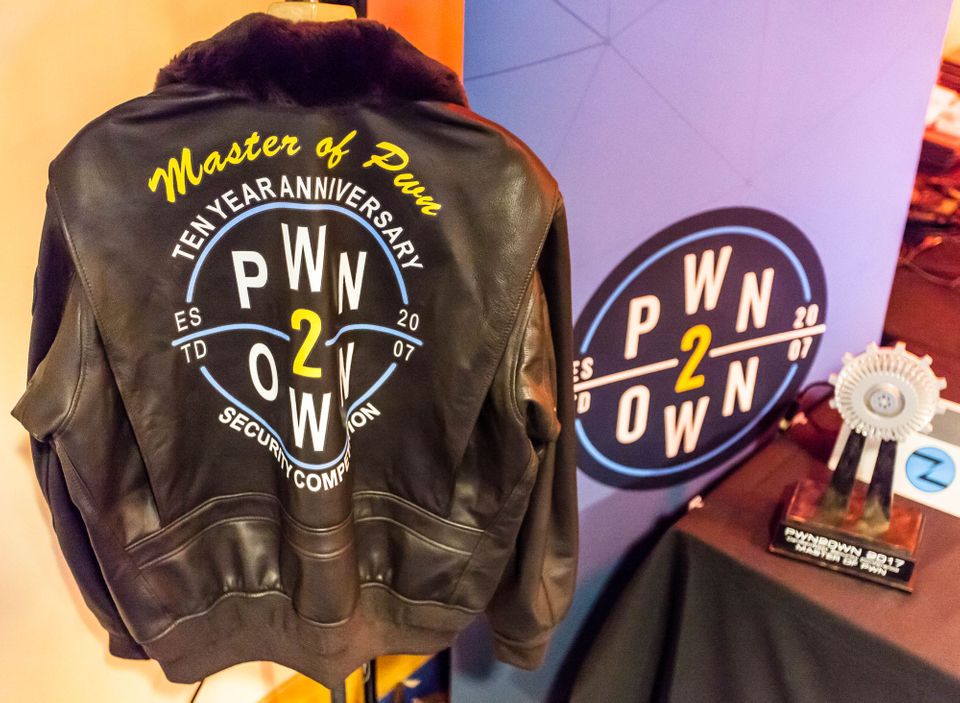

At hacking contests like Pwn2Own, now in its 10th year, individual hackers can shine as they present vulnerabilities and in real time string together hacks of major browsers, operating systems, and other software for cash prizes. Participating companies, meanwhile, can find and recruit badly needed talent, as they build hacker-friendly reputations.

Samuel Gross and Niklas Baumstark of Germany earned $28,000 for their Safari takedown, which was considered a “partial” victory because one of the five security vulnerabilities they used had already been fixed but not yet released by Apple.

READ MORE ON BUG BOUNTIES

Why Apple’s bug bounty is a big deal

Bug bounties break out beyond tech

The dark side of bug bounties

When to disclose a zero-day vulnerability

Survey says: Don’t start with a bug bounty

Gross and Baumstark, respectively ages 24 and 25, also hacked the new Mac Touch Bar feature and said they found even more flaws.

“We had another bug for another upcoming version of Mac,” Gross says. He declined to say whether they revealed that bug to Apple, because that version of the operating system was still in beta, and the company may find and fix the flaw on its own before release.

Their story, which included applying for an export license under the Wassenaar Arrangement so they could transport details of the vulnerabilities from Germany to the contest in Canada without running afoul of international weapons laws, is often played out at computer security hacking contests around the world.

As Gross and Baumstark proved their hacker bonafides to a small room crammed with enthusiastic onlookers and competitors, tech giants Microsoft and Intel announced new bug bounty programs to about 1,000 computer security professionals packed into a hotel ballroom. Microsoft says it has designed its program to encourage attempted hacking of the beta version of its Office productivity suite, and Intel says its program is its first bug bounty ever.

Hacking contests and bug bounties may seem a bit overblown. While hackers are earning more every year in contests and bug bounties, they still rarely earn six figures from them. But the previously unknown security vulnerabilities, or zero-days, that they aim to suss out play an outsize role in consumer security and international politics.

Look no further than the so-called Vault7 CIA documents published by WikiLeaks to see how heavily spy agencies rely on zero-days to achieve their espionage goals, or how the bug bounty black market can pay million-dollar bounties for the rarest of bugs. Yet proponents of aboveboard contests and corporate-sponsored bounties say hackers are still interested in participating in both because they provide longer-term stability.

Bug bounty programs, first created in 1995 and eventually adopted by major tech companies such as Google, Facebook, and Microsoft, began to rise in popularity in 2012, as startups such as HackerOne and Bugcrowd developed businesses around building and managing bug bounties beyond the tech industry niche.

Hacking contests grew concurrently with bug bounties but started becoming headline news when Pwn2Own launched in 2007, with a focus on major platforms. That year, a contestant who hacked a Mac laptop won $10,000.

This year, 11 teams competed for more than $1 million in prize money across four categories. There are now various other hacking competitions throughout the year, including a Pwn2Own contest for mobile devices.

“A typical bug bounty is very active in the first few days, and then dies off after that. A contest is a chance to grab some talent you might not see otherwise.” — Adrian Sanabria, security industry analyst, 451 Research

Neophyte hackers can now establish reputations while earning money for their hacks. But except in rare cases, such as Jung Hoon Lee, aka lokihardt, who won enough money from Pwn2Own to pay his school tuition and rent an apartment on his own, winnings from hacking contests don’t stack up to full- or even part-time work.

What hacking contests can do that standard bug bounties or regular jobs typically don’t is attract widespread industry attention to individual hackers. While Gross and Baumstark say they were more interested in the technical, puzzle-solving aspect of participating in Pwn2Own, they admit that the instant notoriety of a contest victory can be helpful to their careers.

“We want to get some publicity as well,” Baumstark acknowledges.

Documentation of vulnerabilities and exploit chains might sell for double the amount on the black market than what they’d fetch in a contest, says Dustin Childs, the director of communications for the Zero-Day Initiative, which organizes Pwn2Own. But added control over a vulnerability leaves an ethical hacker with more options.

Once an exploit is “burned on the black market, it’s burned,” he says. But if you save it for a presentation at the annual Black Hat computer security convention, or take it to hacking contests in Europe, “you could get a job offer. It’s a long-term investment.”

How companies benefit from hacking contests

Participating companies benefit from contests not just by identifying and addressing their security vulnerabilities faster, but by building a reputation as a business friendly to the hacker community, says Adrian Sanabria, a security industry analyst and bug bounty expert at 451 Research. Their engagement encourages more hackers to find bugs at the company, including through bug bounties, and creates a virtuous circle.

Hacking contests are also great places to scout for talented coders.

“A typical bug bounty is very active in the first few days, and then dies off after that. A contest is a chance to grab some talent you might not see otherwise,” Sanabria says, adding that newer business are scrambling for security experts.

Hacking contests, nevertheless, are facing growth challenges. Childs says the Zero-Day Initiative has yet to figure out how to do an Internet of Things hacking contest without going bankrupt because of the costs and varieties of hackable devices. His team also aspires to develop a car-hacking contest.

There may simply be too much Internet-connected technology now to continually scale this kind of contest. As it is, Sanabria says, companies that want to participate in hacking contests and offer bug bounties can “barely keep up” with the demands of running their business.

Sanabria quotes a joke by comedian Jim Gaffigan to describe how challenging it is for businesses to manage their participation without outside assistance.

“It’s like drowning—and being handed a baby to take care of,” Sanabria quips.