Backing WebAuthn, tech giants inch closer to killing passwords

SAN FRANCISCO—The push to eliminate fraudulent log-ins may depend on whether a Goliath partnership of major tech companies can succeed against a humble but resilient enemy: the password.

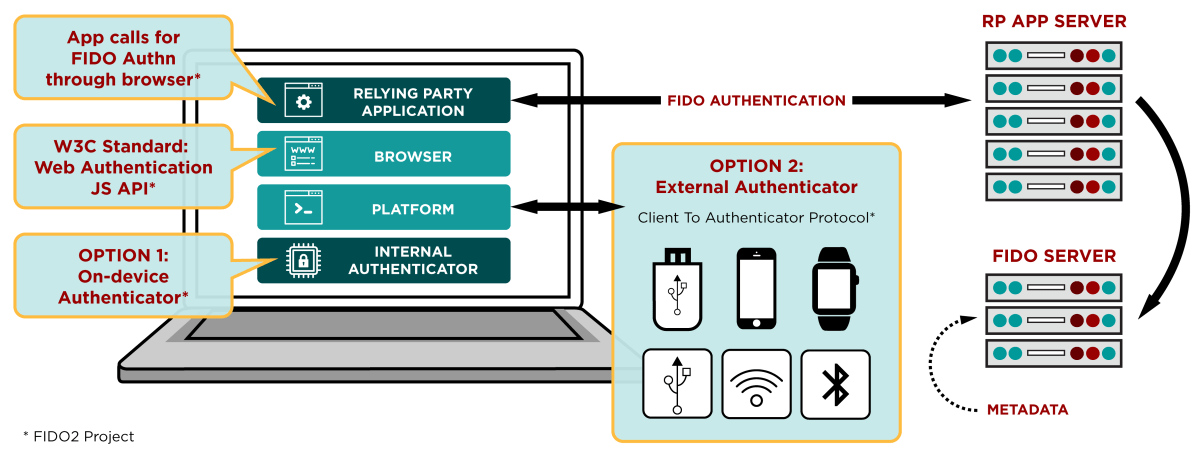

Earlier this month, the standards groups FIDO Alliance and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) announced that online services can begin implementing a new Web authentication standard called WebAuthn into their sites and apps as part of the update to the log-in protocol FIDO2. The current version of FIDO has broad support from big-name financial institutions and tech companies, including Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Salesforce.com, Dropbox, eBay, Aetna, PayPal, Bank of America, and Bank of China.

WebAuthn would allow users to log in to any website or app that supports it with a physical second factor, which could be a device as common as a smartphone, or as uncommon but secure as a two-factor authentication key.

READ MORE ON PASSWORD SECURITY

Shape’s Blackfish could stop password thieves cold

Apple ransom highlights danger of credential stuffing

What to do when your password gets reset

Passwords, hackable yet accessible, are poised to stay popular

How YubiKey could double-lock your online accounts

You’ve been caught in a data breach. Now what?

The WebAuthn protocol can also support various biometric log-ins, including face and voice recognition, fingerprints, and iris scanning. It enables users to register non-password biometric or second-device authentication methods with the service, thus replacing the password. And it works similarly to YubiKeys or an RSA SecurID key fob: When users try to log in, instead of entering a password, they tap the authentication key, or point their face at the device’s camera—no password or personal identification number (PIN) necessary.

At the RSA Conference here on Friday, Google and Microsoft publicly demonstrated for the first time how WebAuthn works. Sam Srinivas, a product management director for Google Cloud who is working to implement the protocol, says broad support of WebAuthn’s physical-factor log-in will put an end to phishing attacks that successfully steal log-in credentials.

“This essentially ends network-based phishing,” he says.

As three of the more than 30 member-organizations of the FIDO and W3C standards groups, Google, Microsoft, and Mozilla say they already have started to build support for WebAuthn into their respective Chrome, Edge, Internet Explorer, and Firefox browsers, as well as their Chrome OS, Android, and Windows operating systems.

Despite enthusiasm for technology designed to replace them, passwords have been remarkably resilient. They are infamous for their appeal to consumers and experts because they’re easy to use: username-password combinations have been Web services’ de facto identity authenticators since their commercialization in the early 1990s. But as resistant as they are to innovation, passwords are equally vulnerable to exploitation.

According to Verizon’s 2017 Data Breach Report, 81 percent of data breaches involved weak, default, or stolen passwords, and 1 in 14 phishing attacks were successful in 2016. Data breaches increased 45 percent from 2016 to 2017, according to the ID Theft Resource Center. But up through 2017, the most commonly used passwords were still the easily guessed “123456” and “password.”

Killing off the password could be revolutionary for reducing online fraud. But the process isn’t likely to happen quickly.

David Bossio, group program manager at Microsoft, told his RSA audience that consumers will be able to use the Microsoft biometric log-in feature Windows Hello with WebAuthn, and he expects support in major browsers later this year. But it’s unclear how institutions such as tech alliances will encourage online services to support the protocol, or what they will do to get two-factor keys into the hands of consumers who don’t already have WebAuthn-compatible devices.

“It’s out of scope for us to get involved in use cases,” says Brett McDowell, the executive director of the FIDO Alliance. But, he adds, the promise of moving away from passwords will encourage companies to sign on “faster than normal.”

That optimism isn’t held by all who hope for the demise of the password. Consider that few of the latest Android devices receive monthly security updates, yet they made up 85 percent of the smartphone marketplace at the start of 2017. How will manufacturers ensure that consumers can use a new protocol, when they already struggle to ensure that their devices receive the latest security patches?

Khad Young, who handles communications for password manager 1Password, told The Parallax in an emailed statement that while FIDO is “probably the most promising proposal in a long time,” driving broad adoption will be challenging.

“The FIDO support is good because passwords are such a weak link, and people hate them. But it’s bad because it gives the big companies more and more control.”—Avivah Litan, vice president and distinguished analyst at Gartner Research

“It requires work from website developers, and it requires a way for people to use their FIDO devices on different devices. It can be hard to get nontechnical folks to adopt a work flow for the sake of security,” he says.

Noticeably absent from the list of major tech companies supporting FIDO2 and WebAuthn is Apple, says Avivah Litan, vice president and distinguished analyst at Gartner Research. While McDowell thinks that Apple will soon join the fray, Litan thinks that the maker of Macs and iPhones will stay out of the consortium of supporters, at least in the near future, “to promote [its] privacy principles.”

Those principles, she says, include guarding customer data from other companies. While WebAuthn bears similarities to the Apple ID log-in system in that it works across devices and platforms, one major difference is that it allows any website or device to use it, Litan says. With WebAuthn, when a consumer uses a major technology company’s log-in system, such as Windows Hello, that company might have insight into what else that person is doing online through WebAuthn.

The prospects of fraud reduction and data sharing across partner organizations helped attract major tech companies that support single sign-ons to WebAuthn, including Google, Microsoft, and Facebook, as well as smaller companies in the business of supporting multifactor authentication, such as Yubico. But data sharing also was a big part of Facebook’s recent scandal.

“The FIDO support is good because passwords are such a weak link, and people hate them,” Litan says. “But it’s bad because it gives the big companies more and more control. That’s what happens when you’re that big. You can roll out solutions that are ubiquitous pretty quickly.”

The death of the password may be nearer than ever before. But it’s not here yet, and the convenience of its replacement may come with unexpected costs.