Primer: Why Google is pushing HTTPS

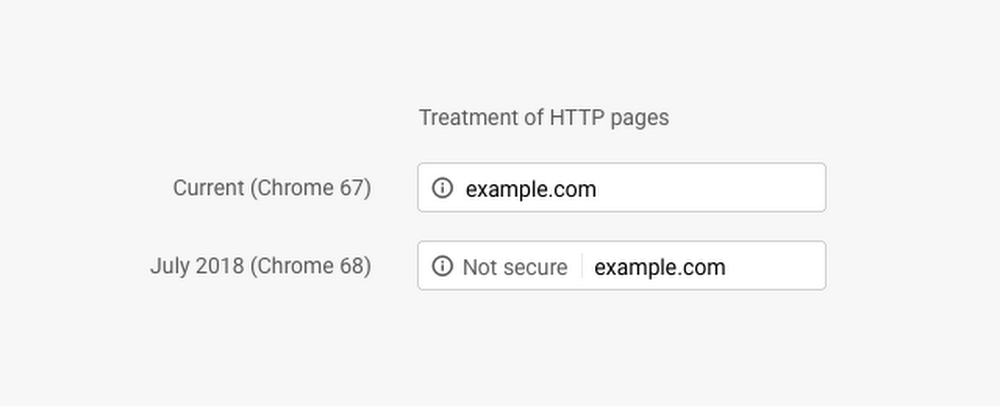

Leading sites hosting services or content as broad as fantasy football, Doctor Who, and search in China have this in common: Google Chrome now marks them as unsafe to visit. As of Tuesday, the browser labels ESPN.com, BBC.com, Baidu.com, and thousands of other sites that don’t use HTTPS as “Not secure.”

It’s the first browser to do so, but because of Chrome’s position as the most popular browser in the United States and around the world, it’s a change that could indicate how browsers will react to security challenges in the future.

The update completes a two-year project to strong-arm Internet companies into transmitting data more safely between websites and users through HTTPS. Google Search already downgrades sites that don’t use HTTPS in its results. And to help spread it to the mobile Web and apps, Google opened registration for the new top-level domain .app in May that may be used only with HTTPS connections.

READ MORE ON BROWSER SECURITY

With .app, Google plans to build a safer Web

Web’s most annoying ads no longer welcome in Chrome

Slowly but surely, browsers are becoming more secure

As browsers accelerate, innovation outpaces security

Web browser security through the years (timeline)

6 browser add-ons to protect you on the Web

Change these 5 settings to improve your browser security

Is Brave the ad-scrubbing superhero the Web needs?

HTTPS, or Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure, encrypts communications between a website’s server and the consumer’s Web browser so that the information sent between them can’t be easily intercepted, or spied on. When added to a website, it provides two services to consumers, says Patrick McManus, principal platform engineer at Mozilla, which builds the Firefox browser.

“HTTPS provides encryption, so nobody can see what’s going on, and authentication, so you’re talking to the website that you think you’re talking to,” McManus says. “That’s where a lot of the shenanigans come into play.”

The secure connection is indicated in the Chrome and Firefox browsers with a green lock icon on the left of the website location bar at the top of the browser. Apple Safari uses a gray icon, as does Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, albeit on the right. Microsoft Edge uses a white icon on the left.

HTTPS, which has been around since the year 2000, was initially used only for online banking and credit card transactions. But in the wake of mass surveillance by governments and organizations around the world, which became headline news as part of the document trove that Edward Snowden leaked in June 2013, technologists, security experts, and privacy advocates have begun pushing to use it much more broadly.

Notably, HTTPS would have prevented Verizon’s “supercookie” from collecting any information on consumers. The FCC in 2016 fined the telecommunications company $1.35 million for failing to inform people about tracking of sites visited via mobile phones using its network—or letting them opt out. HTTPS also prevents Internet service providers from injecting ads into websites without the site owner’s consent, and it can block site spoofing and phishing attacks.

Making HTTPS easier

Consumers can check on which top websites have yet to upgrade to HTTPS without visiting them at Why No HTTPS, a site started by Troy Hunt, publisher of data breach clearinghouse Have I Been Pwned. Hunt has also published a guide to streamline the process of adding HTTPS at HTTPS Is Easy.

The essential part of adding HTTPS is the encryption certificate, a small data file that ties the cryptographic key to the site owner’s details, which can sometimes cost hundreds of dollars. To make it easier (and cheaper) to adopt HTTPS, the Electronic Frontier Foundation spearheaded a movement with Google, Facebook, Mozilla, and other tech companies called Let’s Encrypt that provides the certificate for free.

Hunt recommends Cloudflare’s hosting services because with “mere button clicks,” it helps site owners set up website redirects, configure advanced uses of HTTPS, and fix HTTP references in otherwise secure pages.

Google’s push to encourage site owners to adopt HTTPS has been met with widespread, if not rapid, approval. Adrienne Porter Felt, an engineering manager at Google who spearheaded the company’s push to encourage HTTPS adoption, said at Google’s I/O developer conference earlier this year that in 2015, fewer than a third of all sites loaded in Chrome used it. Since then, HTTPS-encrypted traffic is up across the board on Chrome.

On Chrome for Android, it’s up from 42 percent to 76 percent; on Chrome OS, which powers Google’s Chromebooks, it’s up from 67 percent to 85 percent; and among the top 100 websites, its default usage is up from 37 to 83. Mozilla reports similar growth with Firefox, from 25 percent of sites using HTTPS in 2014 to 75 percent this year.

Nevertheless, more than half of the top million sites on the Internet are still served to consumers’ computers and phones over the insecure HTTP.

For the next version of Chrome, the 69th, Google plans to change its secured-by-HTTPS label from green to black to make it seem more normal to be secure. And for Chrome 70, expected in September, the Not Secure text will change from black to red when consumers enter data into a text field on an HTTP website, in the hopes that the slight change will make the not-safe warning more clear.

While shaming sites with red labels for lacking HTTPS protection may seem like a small change to some people, it could have a big impact on more than just consumer security, McManus says.

“Encryption has become the guardian of innovation,” he says.