How USB sticks help drive freedom in North Korea (Q&A)

PRAGUE—Like not fully sitting on a public toilet seat, a major rule of good computer security hygiene is not to stick random USB sticks, or flash drives, into your computer—you just never know whether they might be loaded with nasty malware.

On the other hand, flash drives, like Porta-Pottys, however unsanitary in perception, often come in handy. They may even be key to bringing a glimpse of freedom to the citizens of North Korea.

That’s the hope of Jim Warnock, at least.

Warnock is director of outreach at the New York-based Human Rights Foundation and the public face of its Flash Drives for Freedom initiative. He and a North Korean activist, who wished to remain anonymous because of his work helping defectors leave the country, say USB flash drives loaded with films, TV shows, ebooks, music, and other digital forms of entertainment into the largely isolated country could promote the spread of free thought among its citizens.

And no, they’re not worried about spreading malware to North Koreans.

READ MORE ON GOVERNMENT SURVEILLANCE

Why (and how) China is tying social-media behavior to credit scores

Hidden inside Dark Caracal’s espionage apps: Old tech

Jennifer Granick on spying: ‘The more we collect, the less we know’ (Q&A)

‘State of Control’ explores harrowing consequences of Chinese surveillance

How Spain is waging Internet war on Catalan separatists

Nunes memo promotes intelligence distrust, not surveillance reform

How to strike a balance between security and privacy (Q&A)

New research explores how the Great Firewall of China works

“We professionally wipe all of the drives that we get, before the new content is loaded on there,” says Warnock, whose oversight of a program called Flash Drives for Freedom began in January. Speaking to attendees of the crypto-anarchist Hackers Congress Paralelni Polis here on October 6, Warnock, added, “I don’t think that the North Korean people really are at a level, technologically, where they need to worry. They’re not watching it on a computer or anything that would have any other personal information.”

Flash Drives for Freedom is one of several international initiatives working on ways to introduce ideas from the outside world to citizens of North Korea, officially known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. The country’s ruling Kim family tightly controls every aspect of life, including food production, business opportunities, travel within the country’s borders, and the flow of information.

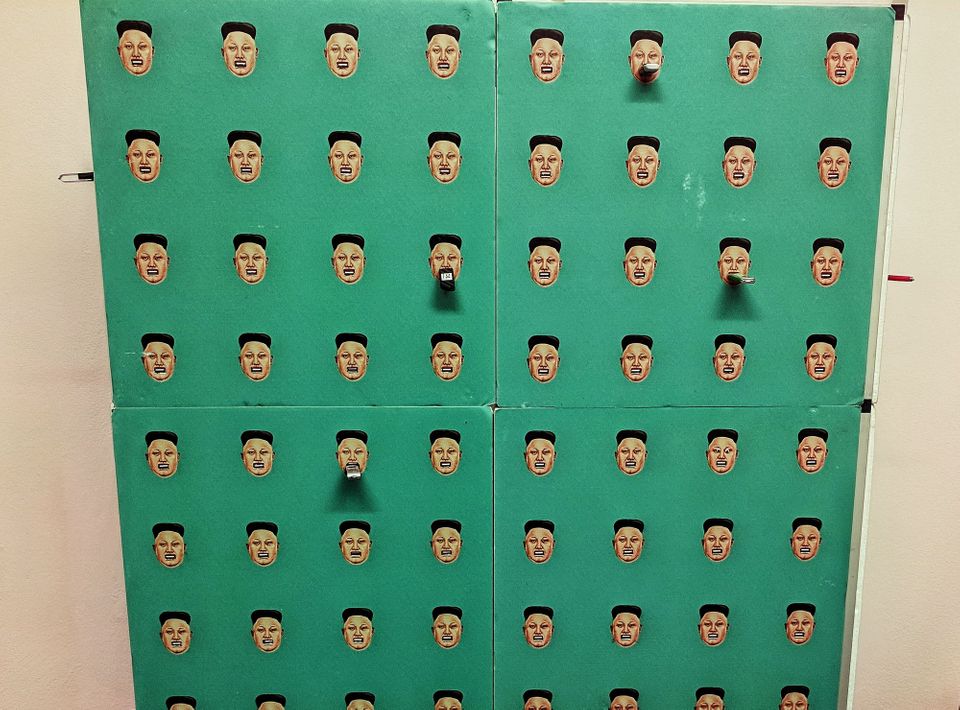

Information flow is the focus of Flash Drives for Freedom’s work. With support from consumer and corporate donations, the initiative has been collecting, infusing with media, and distributing flash drives around North Korea since 2016. It’s best known for its comical, open-mouthed depiction of Kim Jung Il on its donation boxes, which reveals a USB-size slot into which people can stick a flash drive.

Warnock says the initiative is motivated by the core values of its parent organization, Human Rights Foundation, which it implements in a soft, “decentralized” manner. The most effective way to free people who are forced to live under a totalitarian regime, he argues, is to communicate ideas from the outside world through the universal language of pop culture, one USB stick at a time.

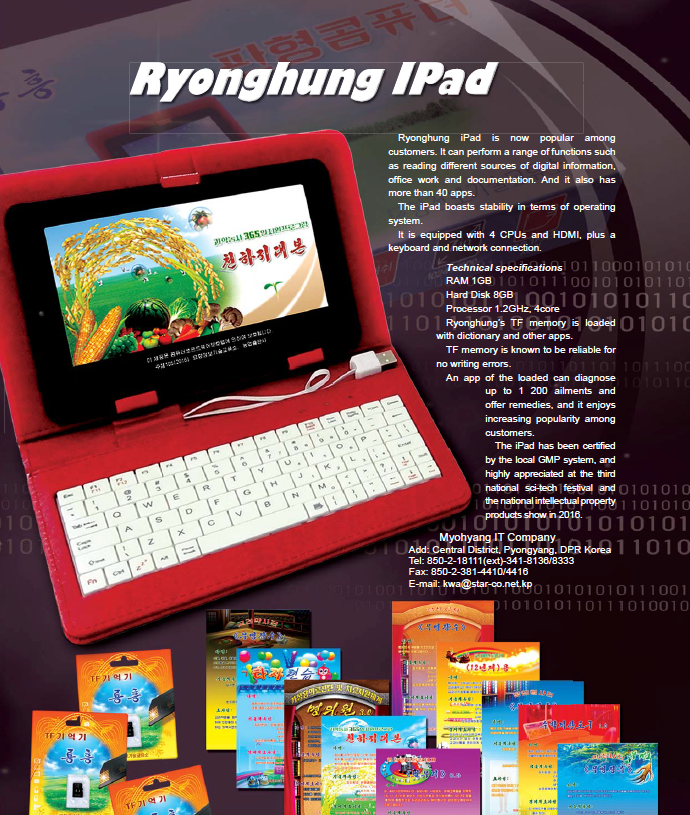

What they are watching it on, says Warnock, is most likely a “notel,” or perhaps a newer Ryonghung iPad-like device. Notels are cheap and popular Chinese-made portable media players equipped with USB and SD ports.

Similarly, the non-Apple Ryonghung tablet computer sports decidedly low-end specifications, comparable to a “netbook” from 2009. According to North Korea’s Foreign Trade magazine, the device is a 250-gram computing slab furnished with a six-hour battery, 512 megabytes of RAM, a 1-gigahertz CPU chip, 8 gigabytes of internal memory, 16 gigabytes of external memory, and an 8-inch screen.

While the network connectivity of the notel and Ryonghung “IPad,” like all other consumer devices in North Korea, is restricted, the devices come with one feature that Flash Drives for Freedom can exploit: a USB port.

In its almost three-year existence, Flash Drives for Freedom has smuggled approximately 200,000 USB sticks loaded with modern entertainment into North Korea by bribing border guards and black-market resellers. And it’s smuggled 40,000 of those, Warnock says, across the 950-mile border with China in the past three months alone.

Parallax readers who wish to donate to Flash Drives for Freedom can contact the organization here. What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation with Warnock and the North Korean activist.

Q: Flash Drives for Freedom has a goal that is almost superheroic in nature: to change the course of a country with simple, ubiquitous technology. What’s the project’s secret origin?

Warnock: Years before Human Rights Foundation was ever involved, North Korean defector groups had been collecting and wiping flash drives, loading them with media content, and smuggling them in, to spread ideas. The activist [and founder of North Korea Strategy Center] Kang Chol-hwan said, “A million flash drives would free my country.”

That started this process with our organization, because Human Rights Foundation been working with these defector organizations from the North Korea Strategy Center, to No Chain for North Korea, to Now Action and Unity for Human Rights, and various other organizations. They were all working in various capacities to try to get information into the country, whether it was via radio, balloon launches, or leaflets. No Chain uses plastic bottles that are full of rice, and now it throws USB sticks into the river that people on the other side are waiting to collect.

One major challenge these organizations have faced is that flash drives cost $10 to $15 apiece at retail—they don’t have the resources to buy a million flash drives. But then they realized that everyone in the Western world has a flash drive laying around that they’re not using.

I’ve been working in this world for four or five years now, and I’m surprised at the lack of knowledge about the actual situation in North Korea. So much of the media focuses on the leader and the government. And nobody really talks about the people.

If we got every single person to send us that one flash drive, we’d have well more than a million. And we could flood the market and push information, as much as possible, into the country. Just to start a conversation.

Since we’ve launched, this grassroots movement has taken on a life of its own—one I really couldn’t predict. These organizations have worked with schools and community groups to run a flash-drive drive for us, for a week or a month, and collect a couple hundred drives here, a thousand drives here. It really adds up.

We’ve just been overwhelmed with the support, but it’s more about the conversation. Even going to elementary schools and starting to talk with kids about how they have a television that they can turn on. Mom and Dad might be controlling what they see, but what if mom and dad were actually the ones that were making the content, too? And that was the only thing that you could ever see? What if that was the only story you were ever allowed to see?

They’re surprised. People just don’t know what it’s like, honestly. I’ve been working in this world for four or five years now, and I’m surprised at the lack of knowledge about the actual situation in North Korea. So much of the media focuses on the leader and the government. And nobody really talks about the people.

Donald Trump made some unusual attempts at engaging with the current North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un, earlier this year. Did that have any impact on raising the profile of getting outside media into North Korea?

Warnock: They were basically just patting each other on the back. Not once did they mention the North Korean human rights issues. They never came up.

What’s really frustrating about that is the fact that Donald Trump had just had a lot of our North Korean activist friends—a lot of our colleagues—at the White House, discussing this. One of our good friends, Ji Seong-ho, was featured at Trump’s State of the Union address.

He told us the story about being a child and trying to steal coal from a train, to sell on the black market, to buy old noodles, so he could eat. I just could not even contextualize that being something that was happening in the modern age. He passed out when he was stealing, was run over by the train, and lost his leg and his hand—they were cut off. He is just an amazing human being.

The entire room was just sobbing. Even the translator was sobbing, just hearing the story.

And Trump held him up as a model for bravery and somebody that escaped as a refugee. Fifteen minutes after talking about this brave refugee coming to South Korea, he’s talking about how refugees shouldn’t be coming to the United States, and how they’re not welcome, and he’s demonizing chain migration. The irony is not lost.

That’s the point, I told her. I want North Koreans to learn, without realizing what they are receiving.

A lot of the defector communities were really optimistic about Trump’s support. To see him go to that summit and not bring up anything after he had been so publicly supportive—I think they were really all just quite disappointed.

How do you know your flash drives are reaching people?

Activist: I actually haven’t met a single North Korean defector who came to me, saying, “All your USBs actually helped me to escape.” I haven’t met that person yet. But I have met so many North Korean defectors saying that watching outside information actually changed their perspective.

Whenever I go back to South Korea, I always meet at least 10 recent North Korean defectors. I buy them a nice meal, in order to get updated on conditions in North Korea.

One time, I met a girl who recently escaped. When she was in North Korea, she was running a small business. After encountering social and political limits on her family and her dreams, she escaped to South Korea, and studied economics at university.

I told her that we smuggle information into North Korea, and she said, “You know what? I hate watching so many movies and dramas. Why don’t you guys send us lectures in business. We want to learn; you need to educate us.”

And I asked her, “How did you get the concept—the notion of starting a business—when you were in North Korea? Where did it come from? From your education from the government? Or from elsewhere? And then I asked another question: From what age did you begin to watch South Korean dramas and movies?

She said, “Oh, maybe, 8?” From age 8, she was exposed to outside information. She’s 28 now.

And she got it! She said, “Oh, now I realize I actually got the idea of running a business in North Korea from the movies and dramas that I watched.” That’s the point, I told her. I want North Koreans to learn, without realizing what they are receiving.

Warnock: We’re not sending in textbooks, but you still learn, by osmosis. You learn by just tacit observation.

So if you’re not sending in advanced economic-theory texts, or something like Cryptocurrency for Dummies, what, exactly, is going on the drives?

Warnock: We put print media and ebooks on the smaller drives, movies and television dramas on the larger ones. The ones that aren’t from South Korea have subtitles or are dubbed. But we also have an offline Korean-language Wikipedia that we can fit on an 8-gigabyte flash drive.

That’s my favorite. Here is basically all of human knowledge in one stick. Start reading.

Does that list include The Interview, the movie which proved devastating for Sony Pictures?

Warnock: We sent in thousands of copies of The Interview. I kept on trying to tweet to James Franco and Seth Rogen, and I was like, “We were using your film to free North Korea. You wanna be involved in this?” But I didn’t get any response. They were under so much pressure already, and it was right after the Sony hack.

We had to edit it down to 25 minutes, because there was some offensive language and nudity that wasn’t going to be palatable to the audience. North Korea’s a very conservative culture, and we really just needed to stick to the whole point of the movie.

But what was really shocking to them was the notion that God would have to sit down for an interview. Why would he have to? Because you’re not allowed to have a religion in North Korea other than the Kim family. They are your God. To think that God would actually need to sit down for an interview and explain himself!

No South Park on these USB sticks, then. Can you explain the process of what happens to the flash drives, from when they’re donated to when they reach the hands of a North Korean citizen?

Warnock: Schools and community groups and organizations hold a drive drive for us, for a week or a month. They collect a couple hundred drives here, a thousand drives here, and it really adds up.

They send the drives to our collection point in Palo Alto, Calif., though for logistics purposes, we’re looking to change that to our offices in New York. Then we professionally wipe them, and send them to our partners in South Korea, who are all North Korean defector organizations. They were doing this work for years before we were ever involved.

Sometimes we buy in bulk through USB Direct or USB Memory Direct. They have manufacturers in China. So we just ship those USBs to the addresses that we give them.

We then use a replicator to copy the media content to 50 keys at once. That’s actually the most time-consuming and difficult process.

Activist: Then we give them to smugglers. They don’t have the passion like we have. The only reason the smugglers take it is to make money. And they sell it and circulate it into the market.

Our goal, in a lot of ways, is to flood the market—to make the outside information in media as cheap and readily available to the population such that anybody who wants it can access it.

I always remind our partners not to give [the drives] away for free. I’m not a philanthropist; I’m a revolutionary. If you give it away for free, they will be suspicious of you. They will question why these people give this thing for free, because there is a market value on USB sticks—I check the price every month. Right now, a 8GB USB costs about $3.80, a 16GB is $5, and a 32GB is $8.

The content on the USB doesn’t affect the price?

Activist: It totally depends on the seller and the buyer, and even the region. So if you sell it right next to the border, the price goes down, of course, because there’s more of them. But if you sell it further in, the price goes up. It’s not something that you can sell on the street. There are buyers, your loyal customers. So there’s no fixed price for that.

And you accept any size of flash drive?

Warnock: You would not believe some of the crazy flash drives we get. There are so many sizes and shapes—even USB keys that are bracelets. We make a point to utilize whatever we can.

Why is smuggling better than drone-drops or just catapulting thousands of flash drives over the border?

Warnock: We have to work within the already established economy. Our goal, in a lot of ways, is to flood the market—to make the outside information in media as cheap and readily available to the population such that anybody who wants it can access it. And they don’t have to decide, “Am I going to eat today, or am I going to see the new Avengers movie?”

The vast majority of the process is happening in a very discreet way on the border. That’s not quite as cinematically appealing, but it’s more effective.

Are you paying the smugglers to take the drives in?

Activist: It depends on the smuggler group. Some groups need extra money for doing their work, and some groups don’t take money. North Korea and China share 950 miles of border, and there are thousands of smugglers there. So it depends on which smuggling route we use.

What’s next? Can Flash Drives for Freedom expand to Flip Phones or Smartphones for Freedom?

Warnock: I think the next step is moving beyond flash drives and moving toward other tech waste. Old smartphones and tablets, and things that we can get into the country that are not manufactured by North Korea, and that are able to connect in different ways.

All over the world, governments are trying to isolate and control access to the truth and to media. North Korea is the worst end-game scenario, the most extreme example. We kind of feel like, if this program can work in North Korea, it could work anywhere.

Lord knows I have two iPhones, old iPhones, just sitting in a box.

In 2018, we have a developed world—a 21st century with information technology. In Western countries, we are using cryptocurrency, and it’s getting popular. But there are countries like North Korea that go backward. It’s a failure in the international community to allow this to continue, to allow 25 million people to live under the rule—the oppression—of one man, one family.