Meet ‘misinfosec’: Fighting fake news like it’s malware

VANCOUVER—The last thing Emmanuel Vincent expected to do with his Ph.D. in oceanography and climate science was fact-checking news reports. But he found a compelling reason to dive into the fraught world of online journalism: He wanted to stop fake news.

As founder and lead scientist of Climate Feedback, a site through which a network of scientists share assessments of media coverage related to climate change, one of Vincent’s most recent victories was in getting the conservative news site The Western Journal in February to pull a column espousing unsupported claims.

Online propaganda campaigns that spread false information about climate science are growing in size and scope, and Vincent sees the trend as a calling to help better inform other journalists and the public about climate science.

“We wanted from the beginning to provide feedback to editors. We have to see if they improve their practices,” says Vincent, who earned his doctorate degree at Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris. But bringing about meaningful change hasn’t been easy, even after working with Facebook “to help them identify sources of misinformation.”

“Sometimes, the newspapers improve,” he says; often, they do not.

READ MORE ON FAKE NEWS AND CYBERSECURITY

Exacerbating our ‘fake news’ problems: Chatbots

How Facebook fights fake news with machine learning and human insights

Opinion: Trump, Putin, and the dangers of fake news

CrowdStrike CEO on political infosec lessons learned (Q&A)

How political campaigns target you via email

Disinformation campaign organizers, of course, seek to influence public opinion about heated news topics well beyond climate change. Facebook groups that Russian operatives used to spread disinformation about other politically charged topics during the run-up 2016 U.S. election commanded immense followings, according to research Jonathan Albright of Columbia University published in October 2017: A group called “Blacktivists” had 103.7 million shares and 6.1 million interactions; “Txrebels” had 102.9 million shares and 3.4 million interactions; “MuslimAmerica” had 71.3 million shares and 2.1 million interactions; and “Patriototus” had 51.1 million shares and 4.4 million interactions.

The University of Oxford’s Computational Propaganda Research Project published a report in July 2018 on social-media manipulation, which most disinformation campaigns rely on to spread various messages. The study concluded that “computational propaganda” campaigns, which use “automation, algorithms, and big-data analytics” to manipulate public opinion, occurred in 48 countries in 2018, up from 28 the year before. All of the countries engaged in the campaigns had at least one political party involved.

Fake news is big business too. The University of Oxford report says that cumulatively, countries across the globe have spent more than $500 million since 2010 on online campaigns intended to manipulate public opinion.

“A defender trying to work out the steps an attacker would have gone through is basically what infosec does.”—Sara-Jayne Terp, data scientist and strategist, founder of Bodacea Light Industries

Vincent says he recognizes that his efforts and potential impact are small, compared to existing efforts to create and disseminate fake news. And so far, there’s been no effective systemic approach to combating the spread of online misinformation or disinformation. (Misinformation generally refers to unintentionally incorrect information, while disinformation means intentionally misleading information. But discerning intent online is no easy task, either.)

Sara-Jayne Terp, a data scientist and strategist with more than 30 years of experience specializing in the impact that computer algorithms have on people and the founder of cybersecurity consulting company Bodacea Light Industries, believes that a key missing component to stopping the online spread of false information, regardless of intent, lies in adopting tried-and-true defensive cybersecurity strategies.

At the CanSecWest conference here in March, where Terp presented her approach, she told The Parallax that efforts to combat torrents of fake news thus far have lacked an “adversarial style of thinking.”

Defenders should be ”trying to work out the steps that an attacker would have gone through to create an incident—and the artifacts they would’ve created as they did that,” she says.

“The reason it works well is because you have an adversary and a defender who’s trying to work out what they’re doing, and that’s exactly what you see in infosec.”

The underlying challenge to fighting fake-news campaigns, Terp says, is that, like computer hackers, disseminators of disinformation only have to score one big hit when using a multipronged strategy to distort facts and create confusion, distract from more important issues, divide their targets into opposed groups, dismiss their critics, and foment dismay in their targets in order to get their message out. People who are trying to stop the spread of inaccurate information, including Vincent, have a much harder job.

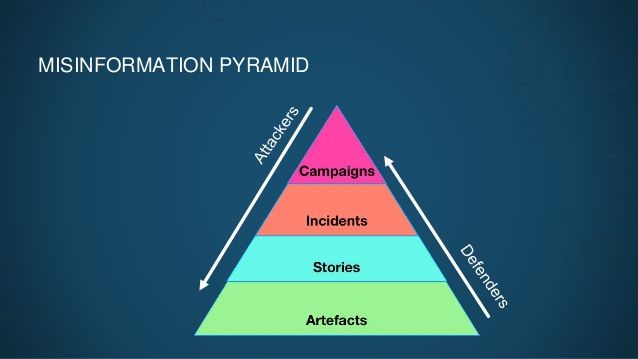

Fake-news dissemination follows a pyramid structure, Terp says. At the top of the pyramid are the campaigns, such as the Russian efforts to influence the 2016 U.S. election. Below that, there are incidents, stories, and artifacts. Whether attackers are trying to spread malware or disinformation, they have to study the people they’re targeting. They have to create convincing artifacts such as images, text, and websites. And they have to get those artifacts in front of their targets.

Those artifacts are exactly the kinds of manipulations the University of Oxford report cites. The fake-news campaigns it analyzed stretch far beyond what can be considered traditional political messaging. In addition to using social media to spread false information, they use illegal data harvesting, micro-profiling, hate speech, and click-bait text, photos, and video to influence public opinion. Disinformation campaigns attempt to reach their targets not just through Facebook and Twitter, but also through messaging apps such as “WhatsApp, Telegram, and WeChat.”

“Bot-like behavior can be exhibited by a program and by a human. You need a combination of human analysts and algorithm analysis,“—Staffan Truvé, co-founder and CTO, Recorded Future

Terp has a term for using cybersecurity strategies to fight the spread of false information: “misinfosec.” And it requires working backward, from the artifacts up to the campaigns, like an infosec red team.

“It’s the idea of red-teaming, putting myself in the other guy’s head and what they need to do. This is about that—thinking from the other side,” she says. “A defender trying to work out the steps an attacker would have gone through is basically what infosec does.”

Other researchers who combat disinformation campaigns we spoke with say there has yet to be a coordinated strategy across social-media platforms that utilizes a red-team philosophy.

Facebook declined to directly comment, but it highlighted a February 2019 study by independent researchers from four universities that indicate a 75 percent decline in fake-news campaigns consumed by Americans in the 2018 election season compared to the 2016 season, and that Facebook’s role in the spread of fake news has also declined.

Three separate reports, respectively published by researchers at Stanford University and New York University, the University of Michigan, and the French newspaper Le Monde, indicate that Facebook’s attempts to minimize the impact of disinformation campaigns might be working.

Twitter did not return a request for comment.

Ahmer Arif, a Ph.D. candidate who researches fake news and social engineering with University of Washington professor Kate Starbird, says that while he worries about “homogenizing” techniques to counter a complex social issue, better structures are needed to counter the impact of online disinformation.

“I absolutely believe that we need some frameworks in combating this stuff. It will probably have to revolve around policy, technology, and education,” he says.

Meanwhile, Staffan Truvé, co-founder and chief technology officer of cybersecurity research company Recorded Future, cautions that any approach will be hard to implement, as platforms such as Facebook and Twitter admit they are often slow to respond to disinformation campaigns. In addition to strategizing, combating organized social-media manipulation will require a mix of human and automated responses, he says.

“Automation is really the only way for the good guys to stay ahead of the bad guys,” Truvé says. “Bot-like behavior can be exhibited by a program and by a human. You need a combination of human analysts and algorithm analysis.”

But fighting coordinated misinformation online is such a new profession that even the terminology used to describe the issues (and players) is still squishy.

“We need a common language, and even the definition of misinformation is still under debate,” Terp says. “We just need to sit and get to the point that’s similar to infosec, where the words (like phishing) have agreed-upon definitions.”

“We have a lot of groups across a lot of fields that we need to bring together,” she says. “The big platforms should be talking to each other, and to smaller platforms.”

The information sharing should be broad and deep, so that it’s not only the topics of false information that platforms are sharing with one another, but also the names of the organizations and individuals behind the campaigns, Terp says. Information-sharing techniques should also allow legitimate objectionable voices to be heard, while minimizing the kinds of manipulations that plagued the U.S. 2016 election.

“It’s not about removing people’s voices; it’s about removing their megaphones,” she says. “You need third-party trusted bodies of information that can share information. Can you imagine not sharing information on a computer virus that’s coming through?”

Disclosure: CanSecWest’s organizers covered part of The Parallax’s conference travel expenses.