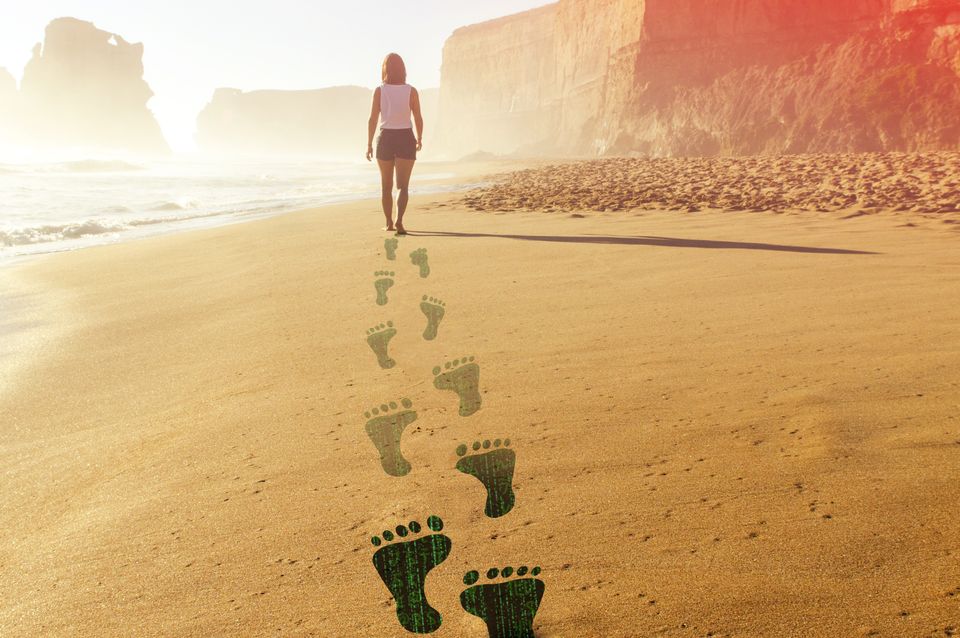

6 ways to reduce your digital footprint

For 15 years, Frank Ahearn has helped people disappear. In the age of the Internet, that’s a tall order.

Ahearn, a privacy consultant and best-selling author, works with clients who have extraordinary privacy needs. Some need to protect themselves from an abuser or stalker, some want to keep their level of wealth private, and others are trying to distance themselves from past business partners.

“They all have something in common,” he says. “Either money, violence, or information.”

Hayley Kaplan, an online privacy expert, is also in the business of helping people reduce their digital footprint. She helps federal and state law enforcement employees protect their identities, and has also worked to make crime victims hard to find. While she and Ahearn focus on extreme cases, they say most people could learn from what they do.

“There’s a chance, down the line, that you’ll run into a situation where online information about you could become problematic,” Kaplan says, such as becoming a victim of identity theft, fraud, or stalking. “People overshare so much online, and they often don’t realize the consequences of it until it’s too late.”

Ahearn and Kaplan use a number of tactics to manage their clients’ online presence. Here’s a look at six strategies you can apply to retain more privacy in today’s digital era.

1. Define what privacy means to you.

How private do you want—and need—to be? Ahearn says people need to determine what privacy means to them. What are you comfortable (and uncomfortable) sharing? How much time are you willing to spend to remove your personal information from various sources? What sacrifices are you willing to make to reduce your online footprint?

“Privacy is something we expect, but it’s not something that’s given to us,” he says. “Everyone has different definitions of what it means and how that plays into their comfort level. How far are you willing to go to ensure your privacy? That’s up to you to decide.”

2. Google yourself.

To see what others can easily learn about you, search for your first and last name in quotation marks, then page through the search results, Ahearn says. Additional searches to consider: your name plus those of friends, colleagues, locations, and years with which you’re associated. And don’t restrict your searches just to Google—try less popular search engines too, such as DogPile and Ask.com.

3. Remove your profile from ghost sites.

Don’t remember that online service you signed up for six years ago? Search engines do, and you’ll usually find reminders several pages into your search when you google yourself, Ahearn says.

“Most people don’t keep track of the sites they sign up for. These ghost sites linger on page 13 or 20 of search engine results,” he says. “Once you sign up for a site or service online, people are making money off your information. There’s no need for that, especially if you don’t use them.”

4. Be smart about social media.

Ahearn staunchly opposes social media from a privacy point of view, and he believes that individuals with privacy concerns should shut down all accounts.

“I understand social media’s appeal, but this is uncharted territory—we just don’t know how our information will be used in 10 years. Once you put something out there, you have zero control over it,” he says. “The website owns your information.”

Kaplan holds a different view. If you choose to partake in social networks, she says, do so understanding the potential risks and know how to use privacy controls.

“Be wise about what you share and don’t share” she advises. Omit personal information like your birthday, location, employment information, and family members, she advises. Be wary of other details, such as your pets’ and children’s names, which could be used to guess security questions.

5. Consider removing personal details on people directories.

Sites like Whitepages, Spokeo, and PeopleFinder aggregate publicly available personal information, such as your past and present addresses and phone numbers. Because they are grabbing this information from a variety of sources, it’s particularly laborious and time-consuming to remove, both Ahearn and Kaplan warn.

“You might delete information from one site, but an aggregator six months later might resurface it,” Ahearn says.

The process, which includes sending emails, opting out online, and even sending snail-mail requests, is tedious and often imperfect, Kaplan says. She estimates that it takes her 60 hours per client to work through opt-outs and to follow up. (See The Parallax’s advice on how to opt out of the most popular lists.)

“There’s just no easy way to do it—it’s a very manual, time-consuming process,” she says. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth trying: “It depends on your privacy needs. If you stop the information from populating early on, you have a greater chance of it not getting into other places.”

6. Think about your offline presence too.

One big mistake people make is viewing their privacy only from an online perspective, Ahearn says. “Most people don’t think about the information they share with utility companies, for example. They ask if you have a contact number, you give it to them, and they might sell it” he says, to other companies that might post it online. “A good chunk of the information that appears online originates offline.”

Although it’s sometimes necessary to share this information, Ahearn says people need to be more aware of the information they share offline—and how businesses do or don’t share it in a broader context. Understanding this is an important step in gaining more control over your information. (See The Parallax’s special report on data brokers for an overview.)