Once again, beware hacked business listings on maps

To intercept calls to the U.S. Secret Service, The New York Times, or Donald Trump’s campaign office, all you need is an online map service.

That’s the message Bryan Seely, a single father of three in Seattle, computer hacker, and former map spammer, has been trying to get people to hear for six years. He first made headlines about mapping services’ vulnerabilities to social-engineering hacks in 2014, when, out of “frustration,” he altered Google Maps to place a snowboarding shop called Edward’s Snow Den at the approximate location of President Barack Obama’s Oval Office desk and went public with it. He followed up a year later with a TEDx Talk on the next iteration of his maps hack.

“People go on Google Maps or Bing Maps, and search for things” like locksmiths and other local businesses, Seely says. “The assumption is that [their search results are] accurate, and that you can’t manipulate that information. That assumption is wrong.”

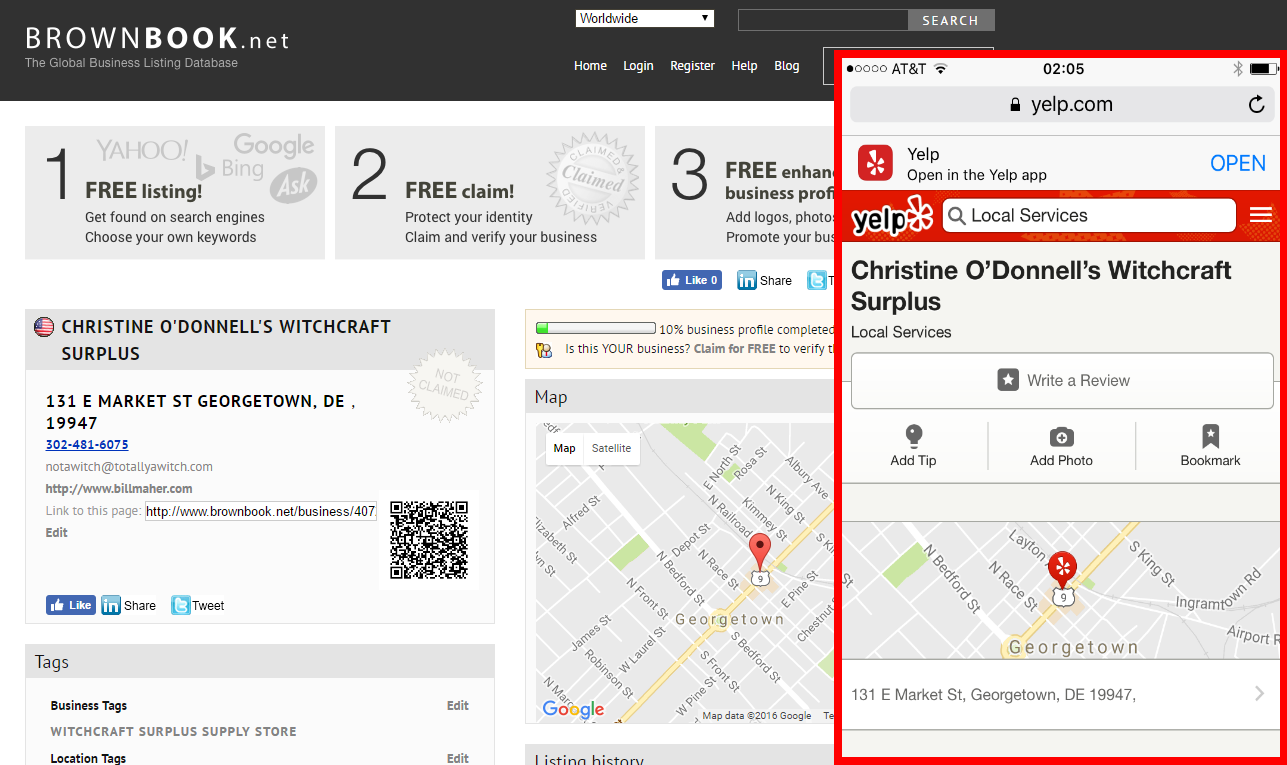

His latest map hacks involve using crowd-sourcing tools from Google, Microsoft, and Yelp to create new or change existing listings on their map services. Despite notifying Google and Microsoft, being the subject of numerous news reports over the years, and even raising the attention of the U.S. Secret Service, the tech companies have yet to address the vulnerabilities he’s demonstrated in the years they’ve known about them.

Because the map providers don’t verify most crowd-sourced listings until at least after they’ve begun showing up in search results, Seely says, he can change phone numbers on listed businesses, as well as move existing listings and create entirely new ones. This enables him (or anybody else using the hack) to forward calls to these numbers to his own numbers and then record them, essentially setting up a wiretap.

Although Seely’s map hacks may sound like the stuff of middle-school pranks, they can have severe consequences, he says. By replacing listed phone numbers with numbers he controls, Seely has received and rerouted phone calls from people assuming that they were directly calling the Secret Service, among other organizations.

“From the Congressman’s perspective, this is an extremely important and underappreciated, undervalued issue.” — Marc Cevasco, chief of staff for Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.)

The danger to consumers, he says, is that scam artists can set up fraudulent or misleading businesses such as locksmiths or car window repair shops. These businesses can lead to local scams, not only charging customers higher rates than what they would normally pay for a service, but also depriving legitimate small businesses of clients.

Seely shared with The Parallax documents claiming to prove, among other things, that crowd-sourced maps host more than 3,000 fraudulent auto glass repair listings, part of a criminal enterprise whose earnings jumped from $1 million in 2011 to $10 million in 2014.

This screenshot of Rep. Ted Lieu’s office listing on Google shows the phone number that Seely controls. The correct number is (202) 225-3976. (Screenshot by Bryan Seely)

A locksmith affected by the scammers told Seattle magazine in October 2015 that the scams are “a big, big problem for honest, licensed businesses.”

Seely’s latest hack starts by tethering his iPhone to his laptop so that the laptop is connecting to the Internet through his phone. That gives it a specific, unique Internet address. He clears his browser cache and cookies, and sets up a new Gmail account. He then signs into Google Map Maker using that account, and chooses a geographic area, such as Seattle.

From there, he starts looking for pending changes to anything in the area, to establish his bona fides as an active, editing member of the Maps community. He approves a few of the changes, makes five or six innocuous changes of his own, then submits a fake business name and a phone number. Finally, he signs out, clears his cache and cookies, and puts the phone into airplane mode.

That takes it off the network. He then turns off airplane mode, which triggers his data provider to give the phone a new IP address. He logs in with a different Google account, reviews a few more innocuous changes, then approves the major submission from his first account.

Seely claims that he can get submitted or updated listings live in fewer than two days. Once those changes are live, he can start intercepting phone calls from people who want to submit news tips.

“That’s how I got The Intercept. That’s how I got The New York Times,” he says.

“Consumers are being harmed by this left, right, and center,” Seely says. “Google and Bing are doing nothing about it. I told them about this years ago—demonstrated it with great risk to my personal self—and they still didn’t do anything.”

Seely showed The Parallax threatening messages he has received from map listings scammers via SMS and online forums in the immediate aftermath of going public in 2014. One such threat he received via anonymized text, after going public with how scammers are gaming Google Maps, reads, “you have big $*%*ing mouth brian and when we find you, you are finished.”

Microsoft refused to confirm the authenticity of emails The Parallax obtained between Seely and the software company in 2014 regarding Seely’s social-engineering hacks on Bing Maps.

Google confirmed the authenticity of similar emails, regarding Google Maps, but did not directly respond to questions about the potential severity of the vulnerabilities.

“We’re constantly improving our anti-abuse detections to help protect users from local-business spam. We’ll take action on spammers when—and frequently before—we detect abuse, by removing their edits and often disabling their accounts,” a Google representative said in an email.

Marc Cevasco, chief of staff for Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.), who has shown a strong interest in tech issues, calls the map manipulation “really disturbing stuff.” Seely has demonstrated to Lieu how he could intercept calls to the Congressman’s phone number.

“From the Congressman’s perspective, this is an extremely important and underappreciated, undervalued issue,” Cevasco says. “There’s just not enough that we’re doing about cybersecurity hygiene.”

Jake Bernstein, who 16 months ago left a long career as an assistant attorney general in Washington state to join a private law practice, says legal action by a state government agency or the Federal Trade Commission, in the form of a case against map scammers or map providers over unfair business practices, is more likely now than before.

“There’s an awareness of [computer] security and sophistication [among] enforcement agencies—a willingness of agencies to take big action against big companies. There’s a better shot now than two or three years ago,” Bernstein says, but he cautions that long-lasting changes will depend on “regulatory pressure” levied against the map providers. “They’re going to do what’s best for them.”

Apparently motivated by a need to atone for his time as a map scammer, Seely says he hopes that he doesn’t have to resort to more extreme measures to get the mapping companies to care. “I could switch Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s phone numbers. But I don’t want to accidentally shoot myself in the head three times.”