Beyond Signal: How Trump staffers could encrypt and archive

Members of the Executive Office of the President, perhaps responding to internal calls for buttoned-up communications, have apparently been using increasingly popular consumer encrypted-messaging apps to chat with one another. In doing so, they have opened a whole other can of worms.

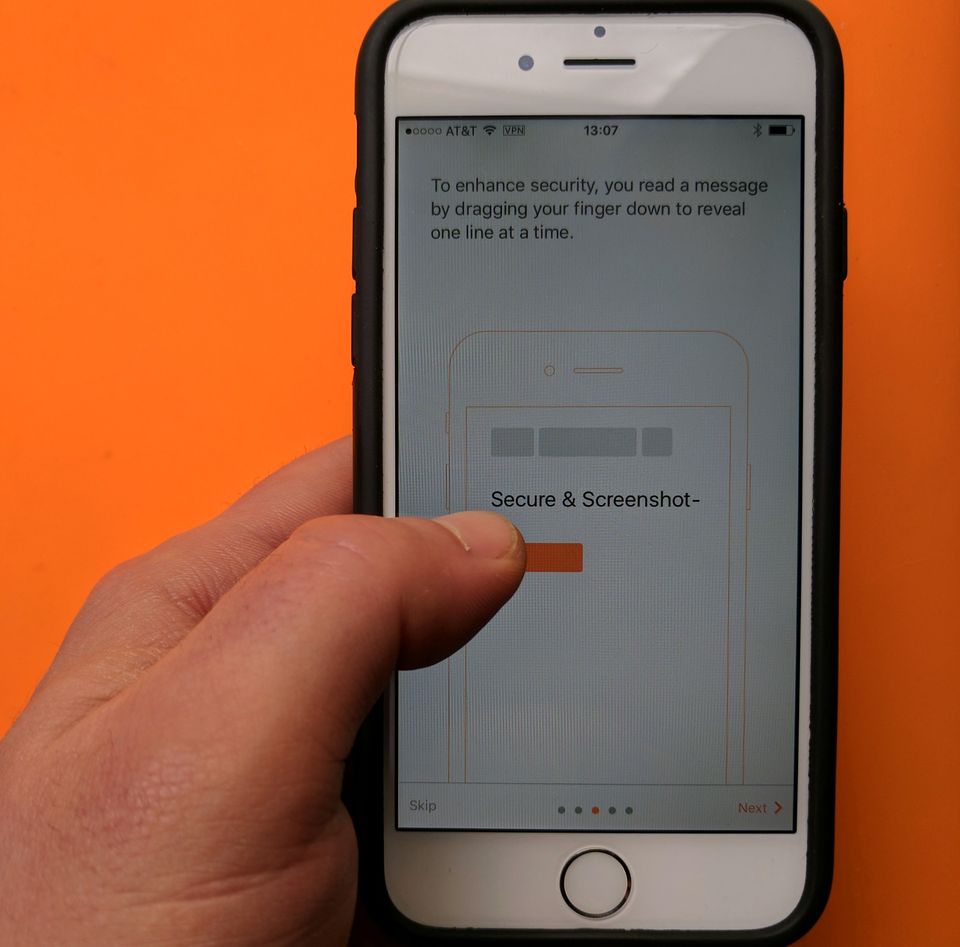

The nonprofit watchdog group Citizens for Ethics and Responsibility in Washington (CREW) has filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration for violating the Presidential Records Act. It alleges that members of the Trump administration are ignoring the record-keeping law by using messaging apps that provide end-to-end encryption, such as Signal and Confide, but that don’t provide the required communications archiving.

“The problem here is that people are setting up their own IT shops and making their own decisions about which apps to use in a government environment.”—Anurag Lal, CEO, NetSfere

Messages sent via these consumer encrypted-messaging apps are inaccessible to official federal archives, according to the suit, because they exist only on the devices of Trump administration officials, from which they can be set to automatically and irretrievably delete.

“The law says that they need to be keeping records of all of these communications,” says Jordan Libowitz, communications director for CREW. “According to reports we’ve seen in the news, they’re using these apps to hide messages. Whether the issue is encryption or deletion, the messages are not being archived, which would put the White House in violation of the law.”

Reports from The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Vanity Fair, and The Atlantic have exposed Executive Office use of encrypted and self-deleting messaging apps for official communications since Trump took office. Presidential communications are not subject to Freedom of Information Act requests while the president is in office. But PRA mandates that unclassified material be made publicly available 5 years after the president has left office and classified material available 12 years after.

Privacy improvements made to messaging apps for consumers and businesses in the years following NSA surveillance whistleblowing by Edward Snowden provided government officials with more secure methods of communication, while decades of scandals over leaked political emails have demonstrated a desperate need to improve intra- and inter-office government communication security. But using secure-messaging apps without providing a means for official communications archiving deprives the public of an official accounting of how the president conducts business and thus violates the PRA, the CREW suit argues.

So how could the White House ensure that its communications remain both secure and archived? Follow the money, advises Chris Wysopal, chief technology officer and co-founder of software security evaluation company Veracode.

Companies in “the financial-services industry, for compliance reasons, [have] to archive all the instant messages between their employees and their customers,” Wysopal says. The Executive Branch could use a messaging tool or method similar to one a compliant financial service uses.

Were White House staffers to continue using free consumer apps to protect their communications with end-to-end encryption, Wysopal says, they could comply with the PRA by adding an official archivist or even an account that can archive messages as a recipient of all official communications.

But the White House should probably switch to an enterprise-grade messaging tool specifically built to meet its security and data retention requirements, argues Anurag Lal, the CEO of NetSfere, which provides end-to-end encrypted messaging to financial and medical companies.

“The problem here is that people are setting up their own IT shops and making their own decisions about which apps to use in a government environment,” says Lal, who was a director of the U.S. National Broadband Task Force for the Federal Communications Commission under President Obama. “The app has to be extremely secure, have the means to archive and audit, the means to control it, and fulfill regulatory obligations.”

Apps like Signal and Confide were never designed to meet those “basic requirements,” he says.

The issues the CREW lawsuit highlight are “not just about new technology,” says Jeremi Suri, a U.S. presidential historian and history professor at the University of Texas at Austin. They’re “also about the personalization of technology.”

Government officials, more and more often, “claim that their records in office are their personal records,” Suri says. “I fear what the Trump administration is doing is attempting to exploit a set of bad practices that they would condemn, if they were being done by Hillary Clinton.”