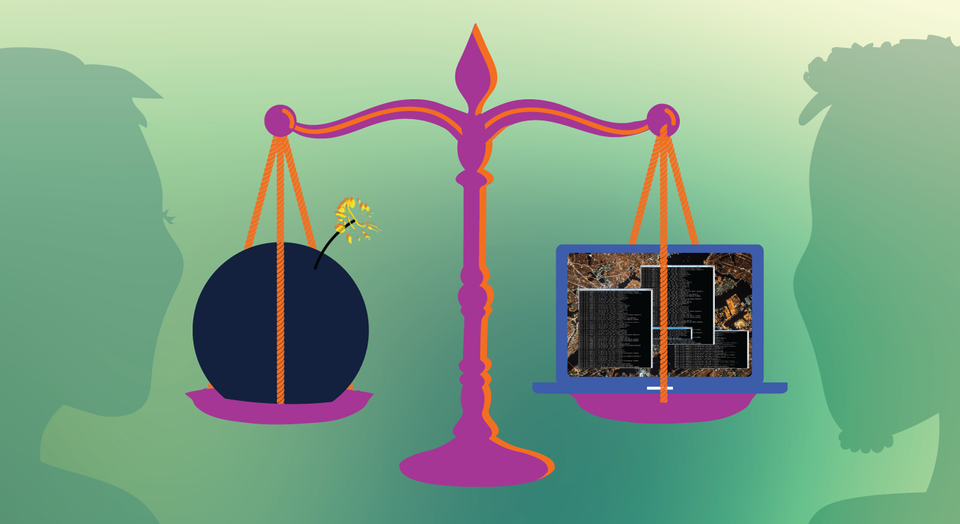

False hack attributions carry dangerous risks

You might have heard that Yahoo has been hacked (more than once). So have Sony Pictures, Target, the NSA, the DNC, the IRS, Anthem, Home Depot, and J.P. Morgan, among many others. You’ve likely been hacked too.

When people outside the information security bubble learn about major corporate breaches, their immediate thoughts often are, How am I affected this time? Who were the hackers? Why did they do it? Those of us on the inside of the sphere are similarly interested, but we are often far more curious about precisely how the hackers got in.

We know that technical details about the original source of entry can tell us a lot about how secure or insecure the victim was before the breach, and how we might respond to protect the systems for which we are responsible.

Even with a lot of technical information, every security pro will tell you that attributing hacks to specific people or organizations—or creating accurate “whodunnit profiles”—is far from an exact science.

Many people mistakenly believe that lone superhackers roam the Internet, targeting victims directly from their evil lairs. This belief leads them to assume that to pinpoint, indict, arrest, prosecute, and finally convict an attacker, investigators simply need to find the IP address he or she used.

That scenario, of course, does not resemble reality.

In the “real world,” coordinated teams of hackers often take precautions—or go to extreme lengths—to cover their tracks as they target specific victims ranging from corporations to government agencies to individuals. And they generally use a diverse set of tools to successfully complete their missions.

Here’s a hypothetical, but more or less plausible, storyline of a modern hacking campaign:

An independent Polish security researcher discovers a zero-day vulnerability. He sells exploit documentation to a United States-based broker for a five-figure sum. The broker improves the exploit, weaponizes it to be used stably and effectively in the field, and resells it to the CIA for six figures. The CIA subsequently integrates the zero-day into its own customized exploit software package. This exploit package, or “cyberweapon,” is later stolen by an insider and leaked to the Russian government.

Then Russian FSB agents hire criminal hackers located in the United Kingdom, give them access to the stolen tools, and instructs them to hack and steal data from a specific large multinational corporation located on servers in two different countries. As part of the operational plan, all of their attack traffic is routed through hacked servers located in China. Later, we find out through a WikiLeaks dump that the criminal hackers were also paid informants of the U.S. government.

OK, now try to attribute that.

Now, let’s say you are somehow in a position to get some piece of evidence of this attack on the multinational corporation. The evidence you have could lead you to a completely different theory of who is responsible.

For example, if you know about the origins of the zero-day exploit, you may argue that the security researcher first used it, then sold it. Or you may know that the zero-day was stolen from the broker and thus assume that it was used by someone else. If you know who eventually purchased the zero-day—the CIA in this hypothetical case—this might lead you to believe that the CIA was involved.

You might also jump to an inaccurate conclusion, if in investigating the attack, you noticed a China-based IP address in the logs—or if you’re an expert in malware reverse engineering, and the sample you’re provided with for this case resembles a sample from another case.

You get the idea? It’s complicated.

As we move into an era of perpetual cyberwar and nation-state cyberwar games, it is very important to understand that attribution is incredibly challenging and error-prone. This is true now, more than ever, as people in top government positions raise the question, “What type of cyberattack should our country consider as an act of war?”

Officials asking this question could be seeking the authority to launch physical attacks in response to online hacks. Let that sink in. After nearly 20 years in information security, very little concerns or surprises me, except this possibility.

A hack attribution—incredibly tough to get right—today runs a high risk of increasing military tensions between two or more countries. This is precisely why security professionals’ responses to attribution reports containing limited technical evidence often include a high level of skepticism. When the stakes are high, we’re going to require more than assurances that the “right” bad guy has been identified.