Hack the Capitol event reminds lawmakers that IoT security needs help

WASHINGTON, D.C.—A small group of information security experts came to D.C. to warn U.S. lawmakers of the risks of poorly secured industrial-control systems. Their two-day Hack the Capitol event took place at about the worst possible time to get Congress’ attention—just as debates over Supreme Court nominee Judge Brett Kavanaugh were boiling over. But in a metaphorical sense, the timing was perfect: Once again, Washington finds itself looking away from cybersecurity.

One charged scenario

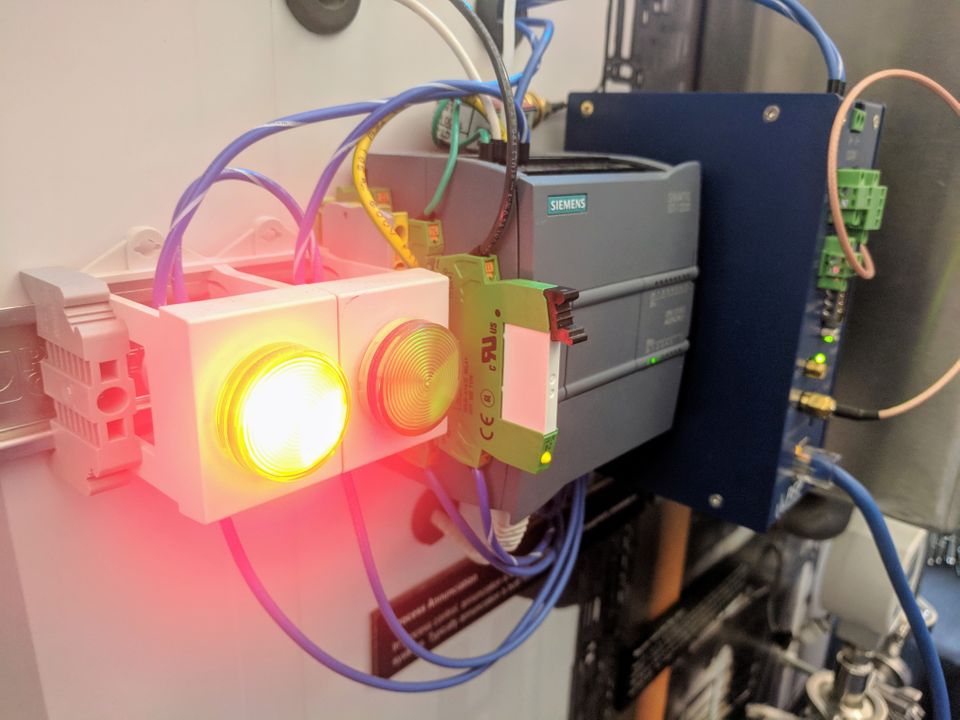

Hack the Capitol, organized by the security group ICS Village, offered a lineup of presentations and talks about how ICS, or industrial-control system, devices can be exploited to cause problems across the real world—and what we might do to stop them. The message throughout was that because this is a complicated puzzle without easy solutions, we’d better get to work yesterday.

Consider, for example, a presentation by Ramparts Security President Colin Bowers on the second day of the conference, September 27, about how attackers could exploit vulnerabilities in electric-vehicle chargers to take down part of a power grid.

The key part of this scenario is the advent of extreme fast charging. XFC hardware can recharge a car or truck’s battery much faster than even a Tesla Supercharger—the Department of Energy predicts that a 15-minute session could impart 200 miles of range, more than twice as fast as Tesla’s technology.

XFC power will be essential to electrifying long-distance trucking, Bowers noted. “In five years or so, we should see 15 of those charging stations at every truck stop,” he said.

But these complex electronic devices will also ship with their own set of attack surfaces, such as remote-configuring interfaces and an over-the-air update mechanism. And they will consume so much power that cycling them on and off rapidly could force power plants to begin going offline to avoid overloading.

Bowers estimated that disrupting 6 XFCs this way would result in 10 percent to 15 percent of a power plant’s output getting dropped, while successfully attacking 11 XFCs would cause a complete shutdown.

He didn’t offer any one solution, instead putting his faith in a variety of collaborative efforts, including research sponsored by the DoE and the National Motor Freight Traffic Association to set open security standards and define best practices.

Answers aren’t obvious

In another Hack the Capitol presentation about threats to the power grid, Idaho National Laboratory grid strategist Andrew A. Bochman offered a realistic—if not always heartening—strategy of preventing the worst outcomes and preparing for the others.

“If you are critical infrastructure, you are a target,” he said. “If you are targeted, you’ll be penetrated; you’ll be owned.”

The answer, Bochman said, is diligently applying consequence-driven, cyber-informed engineering to identifying “the things that cannot fail,” and then engineering as much of the risk as possible out of them.

Or, as he put it: “Think like an attacker, but act like an engineer.”

These defensive measures can include reducing digital pathways into the most critical systems, taking an inventory of what they connect to, and adding backstops and backups for those connected components.

Bochman pointed to how Ukrainian utility technicians in December 2015 were able to recover from a sophisticated and effective cyberattack on the country’s power grid, which Ukraine’s government traced to Russia, by resorting to manual controls of systems that electrical utilities hadn’t yet transitioned to full automation. The utilities luckily hadn’t gotten around to firing personnel with years of manual operations experience.

Stuck in legislative limbo

The day wrapped up with some words of advice from event hosts Bryson Bort, founder of the cybersecurity firms Scythe and Grimm, and a Parallax columnist, and Beau Woods, a cybersecurity innovation fellow with the Atlantic Council.

Bort returned to the theme of ICS hacks being inevitable—stressing the importance of making it easy to identify a breach, respond to it, and patch the underlying vulnerability.

“If we don’t do that, then we are all going to hell in a handbasket together,” he said.

“We don’t know everything that makes a secure system, but we know many of the things that make it fail,” Woods said. Deploying fixes for those causes ought to be the next step, but is not. “What we tend to lack is the political and organizational will to implement them.”

There has been a near-complete lack of activity, for example, on the Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act, a bill introduced in August of 2017 by Sens. Mark Warner (D-Va.), Cory Gardner (R-Colo.), Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Steve Daines (R-Mont.) that would limit the government to purchasing IoT gear that meets security standards.

Bort acknowledged the legislative lag in response to cybersecurity concerns but noted the presence of three House representatives at Tuesday’s sessions, plus “a handful of staffers here.”

“It’s difficult,” he acknowledged. “There are a lot of competing interests.”

And in Washington, as anywhere else, competing interests often contribute to inertia: Continuing to do whatever we’ve done in the past is the logical and predictable outcome.