Primer: When (and how) to dump your Internet provider’s DNS service

The weekend before Thanksgiving, Verizon Communications gave some of its customers in the Washington, D.C., area an unplanned tutorial in the virtues of shopping around for a domain name service, as it experienced a DNS server breakdown.

The Domain Name System is the essential Internet service we almost never need to think about. It automatically and near-instantly translates requests for sites from their domain names to the numerical Internet Protocol addresses of the actual computers hosting them, and DNS servers send the correct configuration details to our computers.

A server outage like Verizon’s might prompt you to drop your Internet service provider’s DNS service. But an outage isn’t the only reason to plug the IP addresses of a free third-party DNS service—the three best-known are Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1, Google Public DNS, and Cisco Systems’ OpenDNS—into your computer or router.

Privacy, then performance

“DNS is by far the leakiest of fundamental Internet technologies that we use,” Joseph Lorenzo Hall, chief technologist with the Center for Democracy & Technology, wrote in an email to The Parallax. Most of the time, no authentication (via the DNSSEC standard) or encryption (via DNS over TLS or DNS over HTTPS) protects these lookups, “allowing your DNS queries to be observed and spoofed.”

READ MORE PARALLAX PRIMERS

Why are Androids less secure than iPhones?

What’s in an APT?

Why people are flocking to messaging app Signal

How to protect your payment apps

Why (and how) to stop cryptojacking

But client support for those security features varies. Firefox, for example, has experimental support for DNS over HTTPS, but Chrome does not yet.

First-party DNS services, especially from larger ISPs, also often treat mistyped domain names as an invitation to show ads on a redirect page. If nothing else, that holds you up from correcting that errant input.

But just as using a virtual private network service shifts your trust issues from an Internet provider that can see every site you visit to a VPN service that can see every site you visit, third-party DNS requires a similar level of faith in that service’s security and privacy measures.

“I’d look at their privacy policies,” Hall wrote. “I know that’s the last thing a consumer wants to hear, but with something like choosing a third-party DNS provider who will see every. single. DNS query you make, you want to be very careful.”

Although Hall and his colleagues at the CDT “don’t endorse products,” he says, he called Cloudflare’s privacy policy “very strong” (it says it doesn’t log client IP addresses at all), ranking Google Public DNS and Quad9 second, and OpenDNS behind those two.

Third-party DNS firms often tout their response times compared to that of Internet providers, but you may not notice any upgrade. Cloudflare, for example, touts the worldwide measurements of DNSPerf testing service to tout its DNS as the world’s fastest. But in North America, that benchmarking test only ranks it fifth.

OpenDNS, meanwhile, sells itself on its content-filtering features.

Jacob Hoffman-Andrews, senior staff technologist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, noted that third-party DNS can also impede the load times of large sites that try to deliver their data from the closest possible server, because your DNS query won’t necessarily come from an IP address near your physical location.

“You may not receive the optimal IP address for the sites you’re trying to visit, which may, in turn, slow down page loads because your packets have to travel a greater distance,” he wrote.

Beware of side effects

You may need to wait for a prolonged DNS outage at your ISP for a third-party DNS service to save time overall compared to the time spent setting up that alternative service—especially if you use a router or an operating system with an especially baroque DNS-settings interface.

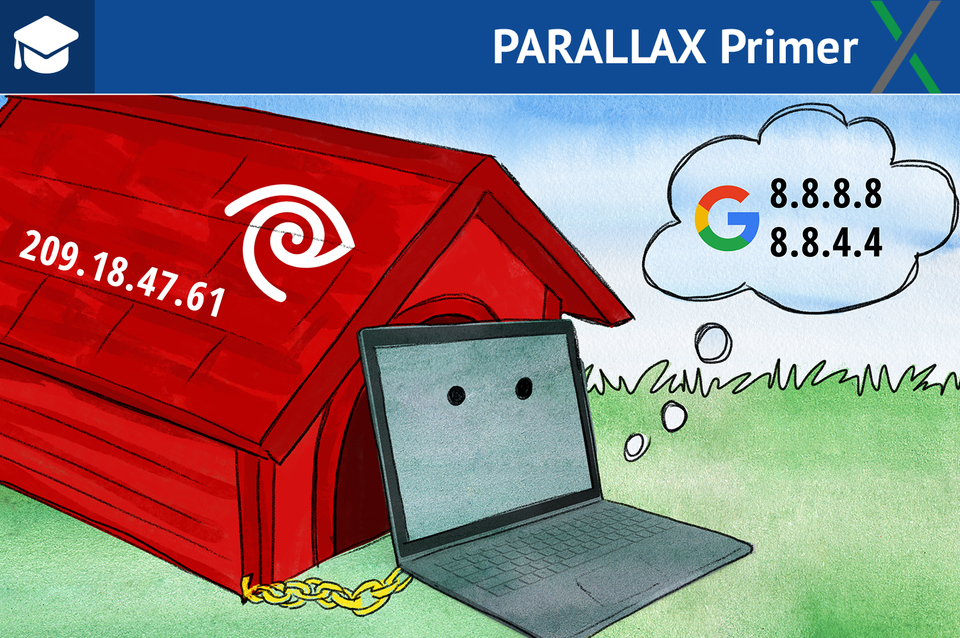

You usually have a primary and an alternate DNS server numerical IP address, plus a corresponding pair of Internet Protocol version 6 addresses, if your ISP supports “IPv6” (which is not a given). Those sets of digits are:

Cloudflare: 1.1.1.1, 1.0.0.1, 2606:4700:4700::1111, 2606:4700:4700::1001

Google Public DNS: 8.8.8.8, 8.8.4.4, 2001:4860:4860::8888, 2001:4860:4860::8844

OpenDNS: 208.67.222.222, 208.67.220.220, 2620:119:35::35, 2620:119:53::53

Changing these settings is relatively straightforward on a Mac, but in Windows, you’ll have to click through a series of fossilized dialog boxes little changed since Windows 95. In iOS, you can adjust them only for Wi-Fi connections, while Android locks them out completely.

Cloudflare provides Android and iOS apps that work around those restrictions by running a local resolver service, at the cost of such complications as having a notification lodged in the Android status bar, unless you hide all notifications from its app. Google also offers a free Android app called Intra that enables third-party DNS use.

It is easiest, in most cases, to change DNS settings at your home router, which will cover not just your own devices but also those of any visitors. But the ease of changing this configuration will very widely with the make and model of your router.

Away from home, the “captive portal” Web log-ins of many public Wi-Fi networks can fail, if you use third-party DNS, as CDT’s Hall reminded me (and as I’ve seen myself). He also advised that on some office networks, local-only domains can become unreachable.

All of these issues led the EFF’s Hoffman-Andrews to advise against third-party DNS in general, unless your ISP is slow at resolving DNS queries, hijacks typos, or blocks some sites.

Fortunately, thanks to Cloudflare and Google using some of the simplest IP addresses possible for their DNS options, your work-around for those problems isn’t much farther than a few repeated keystrokes away, if your provider does become part of the problem.

Disclosure: I also write for Yahoo Finance, one of Verizon’s media properties.