How myth of meritocracy stymies women in infosec

The last thing Carole Fennelly wants to talk about is how women in information security are treated by their male peers.

“I just want to be considered for my work,” she says, adding that she’s been reluctantly complaining for decades about gender discrimination. “I don’t want to be a special snowflake.”

Yet Fennelly, an infosec consultant who has held a range of leadership positions during her 35-plus years in the business, feels that her work hasn’t been given the same level of consideration as that of her male peers.

All 11 female information security professionals The Parallax interviewed for this report reflect that sentiment. Together they have about 400 years of infosec experience suggesting that the industry isn’t a meritocracy. An infosec environment in which women’s good ideas and hard work lead to success, in other words, seems rare.

The numbers support the notion that the infosec industry is tough on women. As of 2012, women held 51.5 percent of all management, professional, and related positions in the United States, according to a Frost and Sullivan report. Yet they held just 11 percent of infosec jobs.

“Having to deal with sexual harassment or a perceived lack of respect brings down the value of the conference,” — Becky Bace, chief strategist at the Center for Forensics, Information Technology, and Security at the University of South Alabama

Despite a surge in conference attendance at major hacker conferences around the United States and Canada from 2010 to 2015, the number of women presenting research or participating on panels at conferences has increased during that period from approximately 6.5 percent to only 7.24 percent, according to an analysis by The Parallax.

Jeff Moss, founder of the Black Hat and Def Con conferences, suggested that women aren’t submitting much work to present, though he cautioned that he and his fellow conference organizers don’t keep track of submission authors’ gender.

Infosec veteran Becky Bace, chief strategist at the Center for Forensics, Information Technology, and Security at the University of South Alabama, meanwhile, suggested that women are tired of attempting to participate in events that aren’t exactly warm to women.

“Having to deal with sexual harassment or a perceived lack of respect brings down the value of the conference,” Bace said.

Slow-grinding gears

Women with a variety of infosec backgrounds report problems that range from the overt, such as workplace sexual harassment, to the more subtle, such as being treated dismissively by male colleagues and managers.

During her time as a systems administrator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1990s, veteran infosec executive and researcher Katie Moussouris faced her desk away from the office door so that visitors would stop presuming that she was the receptionist, she says.

After seven years at Microsoft, Katie Moussouris is suing the company for alleged gender discrimination. Photo by Seth Rosenblatt/The Parallax

Later, she spent seven years at Microsoft as a senior security strategist, founding the company’s “bug bounty” program, which financially rewards hackers for uncovering previously unknown security flaws. She’s now suing the software giant for alleged discriminatory practices toward women.

Microsoft refuted Moussouris’ allegations.

“We’re committed to a diverse workforce and to a workplace where all employees have the chance to succeed,” a Microsoft representative said in an October 23 statement. “We’ve previously reviewed the plaintiff’s allegations about her specific experience and did not find anything to substantiate those claims, and we will carefully review this new complaint.”

“The biggest problem is pay inequality,” Moussouris says. “It’s a subset of the larger ‘women in the workforce’ problem.” And because workplace leaders often fear that talented female employees won’t return after parental leave, she says, they skip over these women when assigning the most rewarding projects.

These problems are not limited to infosec or even the tech world. Earlier this month, actress Jennifer Lawrence wrote a column called, “Why do I make less than my male co-stars?” Both Lawrence and Moussouris concluded that women do not speak up enough to argue for better pay, in part because of a fear of reprisal.

“The traditional male-driven business culture has realized huge profits in security, and brought their culture with them,” Moussouris says. “There were more women in computer security 10 years ago than there are today.”

Hacking, says Jennifer Granick, a privacy attorney and the civil-liberties director for Stanford University Law School’s Center for Internet and Society, “is one of the whitest and most male of any tech field.”

Speaking to a heavily male audience of 6,500 people in August at the business-oriented Black Hat hacker conference, Granick—only the second female keynote speaker ever at the 18-year-old event—indicated that a dearth of women in infosec has led to legal shortcomings in protecting women from online stalkers.

“I know people, particularly women, feel that the law hasn’t been there to help them,” she said, adding that protections against physical stalking “should translate online.”

Hacking gender equality

Gender discrimination is also driving some newer women in infosec toward other industries.

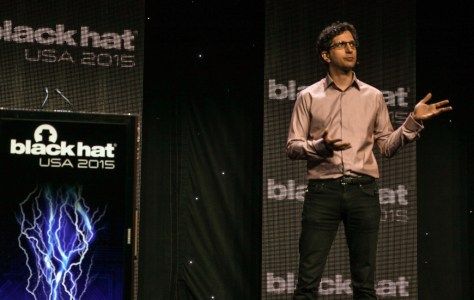

Jeff Moss, co-founder of Black Hat and Def Con, says the conferences are doing more to prevent harassment and encourage women to participate. Photo by Seth Rosenblatt/The Parallax

Jennifer Arcuri, an American technologist who has been working in the U.K. tech scene for four years and recently joined the infosec community, said she is “constantly patronized” by men at infosec conferences. She says that at a conference table focused on picking locks at this year’s Def Con, for example, many male lockpickers made snide remarks about her participation.

Accustomed to such patronization, she says, more experienced women in the field aren’t quick to come to her defense.

“Infosec is harsh to new people,” regardless of gender, says Elissa Shevinsky, a relative newcomer to infosec who runs the company she co-founded, JeKuDo Privacy, and co-organizes the new security conference SecretCon.

“It’s not just that ‘mansplaining’ is wrong, it’s that it’s not working,” Shevinsky says. “It’s not what we expect out of professionalism.”

The struggle to modernize infosec

To be sure, parts of the infosec world are working to change old habits. Industry conference founder Moss said he’s hoping that women’s participation rates at Def Con will increase from what is normally about 10 percent to at least 15 percent.

Women, Moss says, “want fair access.”

To increase accessibility broadly, Moss says, Def Con is working to caption all major presentations for the deaf. Show organizers have also implemented an “acceptable-behavior policy,” he notes, that forbids harassment of any attendees, including but not limited to women, gays and lesbians, and transgender participants.

“It’s one rule for everybody,” he says. “We’re trying to be as open as possible.”

Being more open, Moss notes, doesn’t mean shifting the conference’s focus away from technical issues. While Def Con isn’t opposed to hosting discussions of topics such as discrimination in infosec, as it did last year, “we try not to have a lot of panels on social issues.”

Stanford’s Granick says Def Con is maturing. “People are beginning to understand [that] it’s not cool to be a sexist jerk,” she says. But while she feels “very respected there,” she’s aware of other recent female attendees who “haven’t had as good experiences.”

Indeed, security conferences still have plenty to do to welcome women into their doors and industry, infosec veteran Zenobia Godschalk says.

Earlier this year, Godschalk and colleague Chenxi Wang posed a successful guerrilla protest to get the RSA Conference and Black Hat to ban skimpily dressed “booth babes” on their show floors.

“If I’m getting into security, and at my first conference, half the booths have booth babes,” asks Godschalk, “is that going to make me feel comfortable spending the next 40 years of my life” in this field?

Looking forward

Despite ongoing difficulties in changing attitudes and behaviors toward women, those interviewed for this story are largely optimistic about increasing diversity in infosec and, more broadly, in information technology.

Some point to places like Harvey Mudd College, whose computer science program was overhauled by President Maria Klawe, a trained computer scientist, specifically to attract more women. Among other things, the program swapped instruction in the often-criticized Java programming instruction for the more accessible Python and broadened its approach to solving problems across science.

Runa Sandvik was one of only a handful of female presenters at Black Hat and Def Con this year. Photo by Seth Rosenblatt/The Parallax

Klawe reports that the school saw female students earn 40 percent of its computer science degrees in 2011 and every year thereafter, up from 10 percent in 2007.

Guerilla protester Wang says similar changes in Carnegie Mellon University’s infosec master’s graduate program have attracted more women. The program is now 34 percent female, up from 9 percent in 2003.

Dena Haritos Tsamitis, director of Carnegie Mellon University’s Information Networking Institute, says the infosec industry has a “long way to go” in creating a culture that “attracts and embraces women.”

For industry veteran Fennelly, one indication of such a culture will be the acceptance of equal behavior.

“We’ll have true gender equality when women can be as much of an asshole as men, and it’s not tied to their gender,” she says. “It’s 2015. We have marriage equality. Why the hell are we still talking about gender in the technology field?”

Corrected on Nov. 1, 2015: This story included a typo in the name of Jennifer Lawrence’s column. It is titled, “Why do I make less than my male co-stars?”