How to read a privacy policy

If you’ve never read an app’s privacy policy before downloading it, you’re far from alone. If you’re American, according to a report from Deloitte, you would be part of a 91 percent national supermajority. In this club, you’d undoubtedly find yourself plenty of good company. But you should probably start looking for the exit sign.

Those verbose documents that no one reads—the privacy policy, terms and conditions, or terms of service—typically detail important legal information about your data, including what information the app collects, how the company uses it, with whom it shares it, and how it protects it.

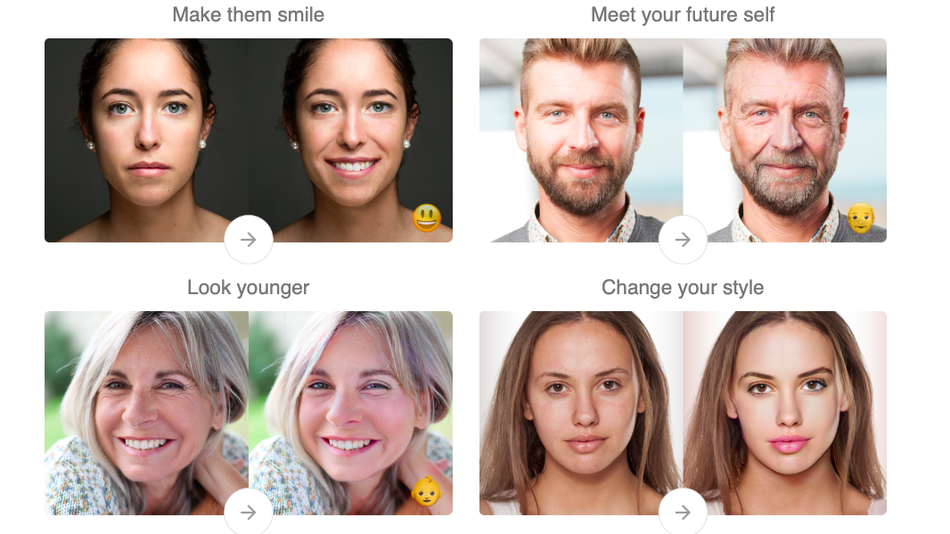

Earlier this summer, for example, if you’d read the terms of FaceApp, you might have noted its Russian origins. You might also have noticed that the app claims near-total control over the photos you upload.

READ MORE ON PRIVACY

Privacy impact of Big Tech breakup far from clear

How updated privacy policies could make GDPR the global standard

Before strapping on that fitness device, check out the privacy policy

How to delete your DNA from popular genetics sites

In post-massacre Vegas, security policies clash with privacy values

According to its terms, “You grant FaceApp a perpetual, irrevocable, nonexclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, full-paid, transferable sub-licensable license to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, publicly perform and display your User Content and any name, username or likeness provided in connection with your User Content in all media formats and channels now known or later developed, without compensation to you.”

As FaceApp’s popularity in Apple and Google’s app stores skyrocketed, privacy experts cried foul. But believe it or not, terms like (albeit not as explicit as) FaceApp’s are relatively common, says Adam Levin, founder of CyberScout and author of Swiped.

“This isn’t much different from what a lot of other social-media apps request,” he says. “They’re generally all very broad.”

Chet Wisniewski, principal research scientist at Sophos, agrees. Attempting to legally absolve themselves from potential lawsuits, he says, app providers typically include as few specifics as possible in their privacy policies and terms and conditions.

“Because they’re a legal document, they’re hard to read and hard to sort out,” he says. “In the FaceApp example, everyone is worried about their data going to [Russia]. The truth of the matter is that this app is doing what most other apps, like Facebook and Twitter, do, if you read their privacy policies. They’re stating that your data belongs to them. Not a lot of people think about this.”

Facebook, for example, says it collects information on “the content, communications, and other information you provide when you use [its] products, including when you sign up for an account, create or share content, and message or communicate with others.” It shares this data—some anonymized, some not—with third parties, which include partners, advertisers, vendors, academics, and, in some instances, law enforcement.

Twitter’s privacy policy states that it collects the data you share with it, which includes basic account information, public information, contact information and address books, private communications, and payment information. It, too, shares this data—anonymized and not—with partners, advertisers, and service providers.

Twitter acknowledges that “your personal data may be sold or transferred as part of” a “bankruptcy, merger, acquisition, reorganization, or sale of assets.” And it says it “may also disclose personal data about you to our corporate affiliates in order to help operate our services and our affiliates’ services, including the delivery of ads.”

While loquacious legalese is tempting to ignore, experts recommend a more practical approach to poring over the legalese in order to help you weigh whether using an app is worth the personal data it’s gaining and potentially sharing.

Search for specific terms

The fastest way to find the information you’re looking for is to perform a keyword search of the document.

On a desktop browser, do this by pressing Control (or Command, for Mac users) + F. On an Android or Apple device using the Chrome browser, tap the menu icon in the upper-right corner, then select “Find in Page” and type in your search term. For Apple devices using the Safari browser, tap the Share icon and swipe along the options until you see the “Find on Page” icon with the magnifying glass.

The following keywords and phrases will flag important details about the company’s data collection, retention, protection, and sharing practices.

- Third parties. While some applications explicitly state that they will never share or sell your information to third parties, others may disclose that they will share your data with its advertising partners or “affiliates.”

- Except. While a document may state that it does not share your data with third parties, some will include exceptions in the next sentence, Levin says. “It’s important to know what they won’t do, but it’s equally important to know what comes next,” he says.

- Retain. Search for details that reveal how long the company stores the data it collects about you. Wisniewski says it’s reasonable that app makers keep your information for a short period of time, but consider it a red flag if they disclose they have the right to retain data in perpetuity. This may indicate its plans to mine your data.

- Delete. App users should disclose under what circumstances or after what period of time they will delete your data. This indicates that the company has a well-thought-out data retention process, Wisniewski says.

- Opt out. Reputable app makers will give you the option to opt out of or turn off a particular setting, Wisniewski says. Sometimes these processes will require you to email them directly or even mail a letter stating your intentions.

- Store/storage. Know how the company plans to store your data safely. Businesses that collect data on users located in the European Union, for example, must adhere to the General Data Protection Regulation, which, among other things, ensures safe security practices. This isn’t the case in the United States, though more states are enacting similar laws.

Alternatively, Wisniewski recommends visiting Terms of Service; Didn’t Read, a project associated with the Electronic Frontier Foundation that rates the terms of service and privacy policy documents for many popular Web pages and apps. It also offers a browser extension. Its ratings—which range from Class A, or very good, to Class E, which is very bad—detail which elements of its privacy policy or terms of service have contributed positively or negatively to its score.

“All consumers must understand the threats, their rights, and what companies are asking you to agree to in return for downloading any app,” Levin says. “We’re living in an instant-gratification society, where people are more willing to agree to something because they want it right now. But this usually comes at a price.”