Is doxing ever appropriate?

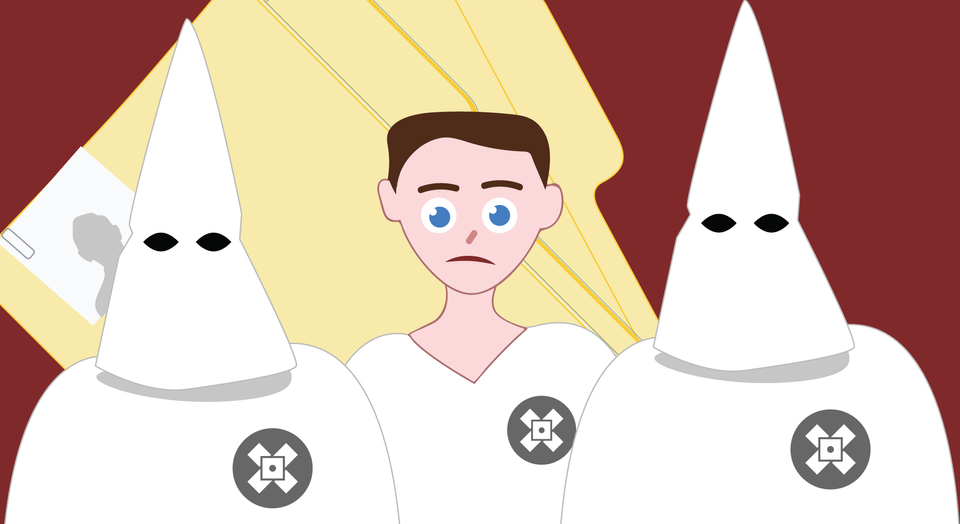

At the end of October, the hacker activist group Anonymous threatened to publish the personal information—or “dox,” in Internet slang—of Ku Klux Klan members. By the middle of November, Anonymous had published the names and at least one piece of contact information for several hundred alleged members of the white-supremacist group.

Publicly revealing the names, Facebook pages, and in some cases phone numbers and home addresses of KKK members was a privacy violation, to be sure. And under federal law, it was illegal. But was it justified?

“Doxing” began in the 1990s as “a way of informal policing by the hacker community,” says Molly Sauter, an Internet historian and researcher who focuses on hacker culture, digital activism, and how technology is portrayed in the media. “With Anonymous, it’s sort of the same. It’s still community policing, but now the community is everyone.”

Most forms of computer-based harassment are illegal in the United States under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. That includes often-used Internet revenge techniques such as doxing; SWATing, in which the attacker tricks the police into sending a SWAT team to the target’s house; DDOSing, which blocks access to a website through a distributed denial-of-service attack, the Internet equivalent of a sit-in.

“We don’t have an understanding of how the Internet multiplies personal power yet,” — Molly Sauter, Internet historian and researcher.

It’s very difficult for academic or law enforcement organizations to keep track of trends in doxing, SWATing, or DDOSing. Only high-profile incidents get reported in the media, such as the Anonymous attack on the KKK, or when security reporter Brian Krebs was subjected to repeated SWATings.

While Anonymous is following vigilante footsteps dating back at least to medieval France, the power of the Internet has changed how communities regulate their members.

“We don’t have an understanding of how the Internet multiplies personal power yet,” Sauter says. “Though mob policing has a very strong history, on the Internet, it breaks the laziness barrier.”

The law, community policing, and the slow pace of change

As technology has made community policing easier, computer crime laws haven’t evolved to keep pace with the people they govern, says Michael Tanji, who worked on information warfare, strategic warning, and digital-media exploitation at the Defense Intelligence Agency.

Tanji contrasts the Steubenville High School rape case, where the town protected its high-school football team players against allegations by a teenage girl that she was raped multiple times by them until the players’ identities were outed by an Anonymous-connected offshoot, to multiple incidents of teenagers finding themselves charged with possession of child pornography when caught texting each other naked selfies. The law equally treats using a computer to expose someone’s identity and sending nude photos of your underage self, Tanji says.

Advanced online community-policing techniques don’t necessarily achieve their desired outcome, either. While Anonymous published a video claiming that some members of the KKK had left the group after being exposed by an earlier doxing effort, people who have been known as white supremacists or nationalists for decades aren’t likely to change their views.

One such person is Don Black, who founded the Stormwatch white supremacist website in 1995.

The November doxing “was just a hodgepodge of public information about people who’ve indicated they were pro-White,” says Black, who describes himself to The Parallax as a “pro-White activist” who hasn’t been a member of the KKK “since 1987.”

Black says these days, “any kid can call himself Anonymous” and play Internet vigilante. Tagging the KKK doxing operation with ”#OPKKK, Hoods Off, or whatever they called it,” he says, “was silly.”