Lawmakers to spar over sunsetting spy law

Surveillance programs deemed by supporters as the “crown jewels” of the intelligence community rely on a U.S. law that expires in December. As some lawmakers push for a permanent extension that overrides the law’s year-end sunsetting, others are pushing for a revamp, arguing that it authorizes Internet-based surveillance that violates the privacy of millions of people.

Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act authorizes the National Security Agency to run warrantless foreign-surveillance programs like Prism and Upstream.

Defenders of Section 702 surveillance have called the law essential to keeping the United States safe from terrorist attacks. Among them, Dan Coats, the U.S. director of national intelligence, says it’s among the intelligence community’s most precious tools. And Bradley Brooker, acting general counsel of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, says the surveillance programs it authorizes produce “significant intelligence that is vital to protect the nation against international threats.”

With endorsements like those, you’d think that reauthorization and a permanent extension of the law would be a slam dunk. Even President Donald Trump, who has complained about intelligence leaks potentially related to Section 702 programs, has said he supports reauthorization without any changes.

But privacy advocates in Congress are threatening to oppose reauthorization without major reform. The implication is that existing Section 702 surveillance programs could be shut down without new privacy protections in place.

“Government surveillance activities under the FISA Amendments Act have violated Americans’ constitutionally protected rights,” the conservative House of Representatives Freedom Caucus said in June. The group of Republicans opposes reauthorization that “does not include substantial reforms to the government’s collection and use of Americans’ data.”

The debate about Section 702 is “far from over,” says Neema Singh Guliani, a legislative counsel with the American Civil Liberties Union. “An effort to sort of ram through some sort of straight reauthorization that doesn’t address some of the core concerns about the program, I suspect, is going to face a lot of resistance.”

Critics see several problems with the existing Section 702 programs:

- No court warrant: The U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court approves Section 702 surveillance requests by the U.S. attorney general and the director of national intelligence to target people “reasonably believed to be located outside the United States” as a way to acquire foreign-intelligence information. But no court goes through a warrant process to examine evidence on whether targets of the surveillance are engaged in criminal or terrorist activity.

- Incidental collection: Even though the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act requires the NSA to target the communications of foreign suspects, the emails, text messages and other communications of U.S. residents are also collected when they communicate with overseas targets. The NSA is allowed to keep communications swept up in the so-called incidental collection.

- Searches of U.S. communications: The FBI and other law enforcement agencies are allowed to search incidentally collected U.S. communications for evidence of crimes unrelated to terrorism or international espionage. Critics complain that these so-called backdoor searches run counter to the intent of the FISA law and violate the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution.

- Number of U.S. residents affected is unknown: The NSA doesn’t provide numbers of U.S. communications swept up in the Section 702 surveillance programs. Despite promises Coats made earlier this year, intelligence officials have yet to provide even an estimated breakdown. Searching through the database could violate the privacy of people whose communications were swept up, and it would be difficult to tell an email user’s nationality in many cases, officials have said. ODNI’s Brooker told senators that NSA officials have yet to find an “accurate and cost-effective method” to tally the incidentally collected U.S. communications.

- “About” collection: Until recently, the NSA has not only collected the communications of foreign suspects and the people they talk to, but also communications about those foreign suspects. So if an email or text message mentions the name or email address of a foreign terrorism suspect, the NSA could collect that communication, even if the sender and receiver were not suspected terrorists. In April, the NSA suspended the controversial “about” collection because of a violation of FISA Court rules, but intelligence officials have said they are working on a way to comply with the court and resume collection. However, even intelligence-friendly Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) is pushing to permanently end “about” collection.

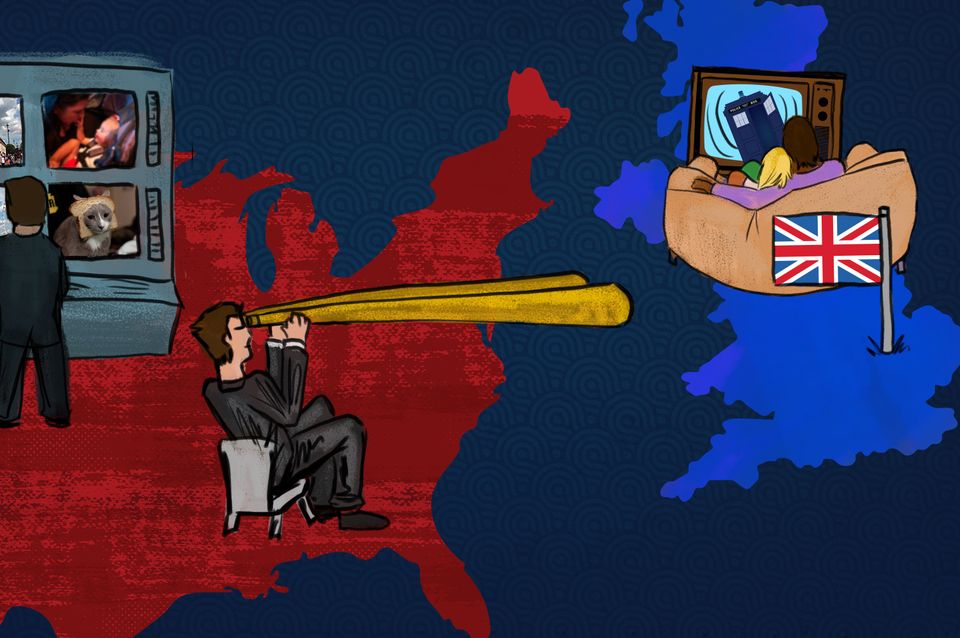

- Widespread foreign surveillance: While most U.S. lawmakers have focused on Section 702’s impact on their own constituents, other critics worry that continued widespread surveillance of people overseas will prompt consumers and foreign governments to distrust or avoid U.S. technology vendors.

The backdoor searches of U.S. communications and the “about” collection have been the most controversial pieces of the Section 702 programs, so look for strong pushes to change those practices. However, Congress needs to have a broader discussion about the limitations of the surveillance, argues Sean Vitka, counsel at digital-rights group Fight for the Future.

“For what can the government use this immense power?” he says. “Currently, anything related to foreign affairs is fair game to be targeted under Section 702, and that is clearly far too broad. If Congress reauthorizes 702, it should be strictly limited to major threats to the United States.”

A reduction in the scope of the surveillance programs could help alleviate privacy concerns from residents of both the United States and other countries, adds Michelle Richardson, a privacy counsel at Center for Democracy and Technology. Lawmakers should consider reining in the law’s authorization of “spying for generic foreign-affairs purposes” such as intellectual-property protection, she says.

Still, supporters of Section 702 aren’t likely give up the crown jewels without a fight.