Most phishers using Gmail are actually Nigerians targeting Americans

SAN FRANCISCO—Turns out the phisher stereotype of the Nigerian “prince” who says he’s looking for a safe place to store his money isn’t that far off the mark. When two Google security team members searched for phishers who use Gmail to temporarily store stolen account log-in credentials, they found about 19,000 of them—and most actually in Nigeria.

After modifying Gmail’s anti-abuse detection systems to look for phishing-kit code signatures, Neal Mueller and Collin Frierson detected more than 10,000 phishing kits in use between March 2016 and February 2017. Collectively, those kits were instrumental in stealing at least 12 million account credentials, they said at the Security BSides conference here Monday.

READ MORE ON PHISHING ATTACKS

How to avoid phishing scams

Parallax Primer: How to dodge a spear-phishing attack

Parallax Primer: What’s in an APT

Your old router could be a hacking group’s APT pawn

How YubiKey could double-lock your online accounts

“We believe this is a low estimate of the total number [of accounts] that in a single year were [compromised] by adversaries that were using these phishing kits,” Mueller says. “We as Americans in America are targeted by phishing kits more than the rest of the world.”

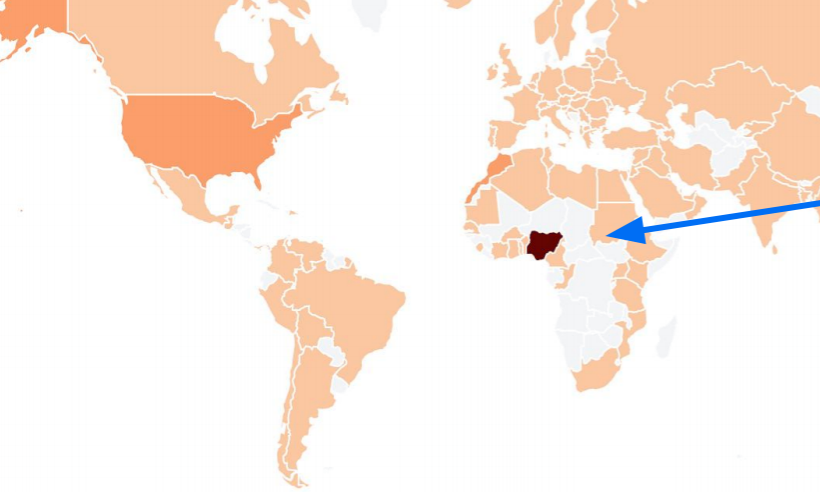

Mueller and Frierson found that 41 percent of the account hijackers they found using Gmail to phish for log-ins were operating out of Nigeria, and 50 percent of them were targeting people in the United States—much more so than any other country. South Africa was the second most targeted country, hosting 4 percent of targeted accounts.

Mueller says the computer code powering most of the phishing kits they found has remained “unchanged in 20 years.” Phishing kits are packages of malicious software used to steal and sell account log-in credentials, often on the Dark Web. Use of a phishing kit is often the first volley of an advanced persistent threat.

To be clear, Mueller and Frierson’s findings pertain only to phishers who use Gmail. Phishers also use other platforms, including Twitter and Amazon Web Services, to phish or to store phished log-ins before moving (and ideally selling) them.

Statistics regarding phishing generally bode well for hackers who use it to steal credentials—and not so well for the plethora of consumers who don’t practice good password hygiene. According to a 2015 report from password manager maker SplashData, the two most common passwords that year were “123456” and “password,” both easy to guess. And according to the 2017 Verizon Data Breach Report, phishing sites disguised as legitimate log-in pages succeed 43 percent of the time, and 76 percent of account exploits occurred because of weak or stolen passwords.

Mueller and Frierson say Google has proactively reset the passwords of 67 million Gmail accounts to protect users it suspected had been targeted by phishers. And Mueller says consumers who are worried about phishing attacks should do the following three things:

First, if you think that you might have fallen for a phishing scam targeting your log-in credentials, don’t wait for Google to reset your password.

Second, use two-factor authentication so that if your password gets phished, and neither you nor Google is aware of it, your account log-in has a second layer of protection.

Third, the single best way to protect yourself from getting phished is to have a physical second-factor key, such as a YubiKey, because it’s very hard to intercept and fake a second-factor code generated by a physical key. These physical keys are often recommended to high-profile targets and consumers who want a simpler way to get that one-time code than from an authentication app or over text message, Mueller says, but everybody should be using them.

YubiKeys and other similar pre-configured USB authentication keys, however, face an uphill climb to broad consumer use. YubiKey sells its cheapest model for $20, which most people don’t consider cheap. Eva Galperin, director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, says she’s never seen a YubiKey in use in a country with a repressive regime like Egypt’s, where activists could highly benefit from them, and she isn’t optimistic about their global adoption.

“Unless you can make YubiKeys ubiquitous and cheap, you haven’t solved the problem,” she says.

When asked what Google is doing to help distribute the keys, Mueller simply responded, “We’re working on it.”