RCS delivers new texting features—and old security vulnerabilities

TOKYO—Google is aggressively boosting a new technology standard for text messages called RCS that it thinks should replace SMS around the world. But first, tech giants and telecommunications network providers will have to fix its major security flaws, researchers say.

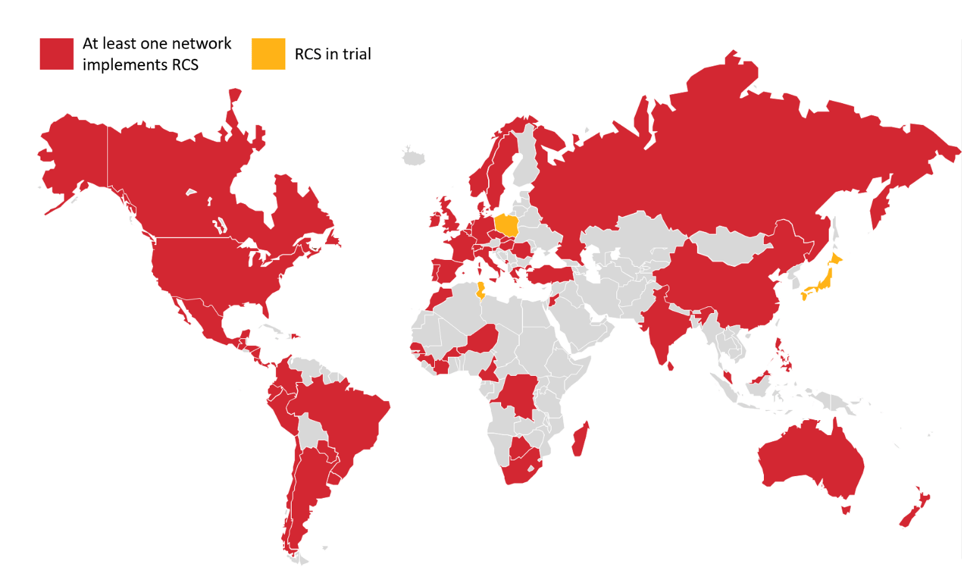

RCS, or Rich Communication Services, brings a feature boost to the 30-year-old Short Message Service standard to make texting more like messaging with iMessage or WhatsApp. RCS data is sent using an Internet address, which means that consumers whose mobile network providers support RCS (available on all four major U.S. networks, as well as more than 100 networks in 67 countries, many in Europe) can send and receive messages, even when mobile network data is unavailable over Wi-Fi; they can receive “message read” notifications; they can send and receive high-quality photos and video; and they can see a three-dot ellipsis notification when the person with whom they’re texting is in the process of writing a message.

Unlike similar but proprietary messaging services like those made by Apple and Facebook, RCS is designed to be an open standard that any tech company or network provider could support. Google has been advocating for RCS since 2015, when it acquired Jibe Mobile, the startup that invented the standard. RCS underpins a version of Google’s Chat messaging app that the company debuted in the United Kingdom and France in June, and is now pushing globally.

READ MORE ON PHONE SECURITY AND PRIVACY

Android Q adds privacy, fragmentation

Google Play is an ‘order of magnitude’ better at blocking malware

Get a new phone? Consider your Fifth Amendment rights

For $3,900, DriveSavers says it can open locked smartphones

Primer: Why are Androids less secure than iPhones?

How to FBI-proof your Android

How to wipe your phone (or tablet) for resale

At the PacSec conference here in November, researchers at Berlin-based Security Research Labs presented security vulnerabilities in RCS texts and calls the company’s founder and CEO, Karsten Nohl, had discovered. (They also presented their findings last week at DeepSec in Austria, and plan to present an “extended set” of their findings again on Wednesday at Black Hat Europe in London.)

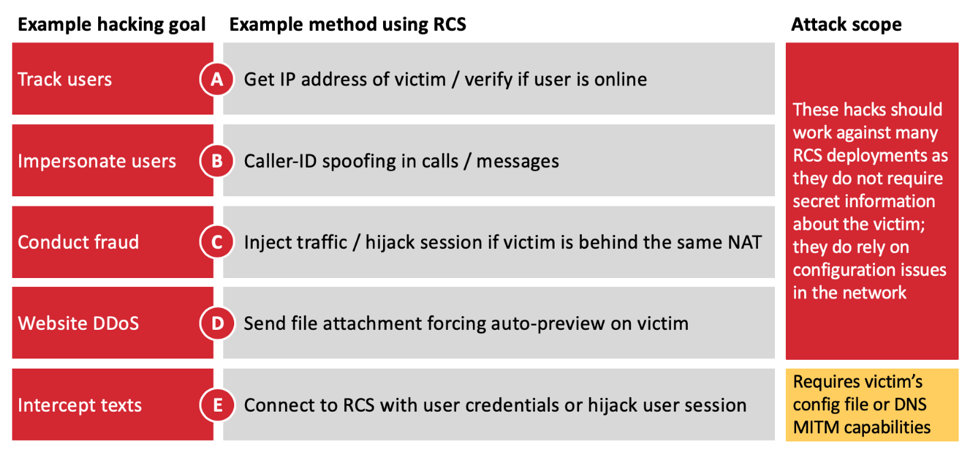

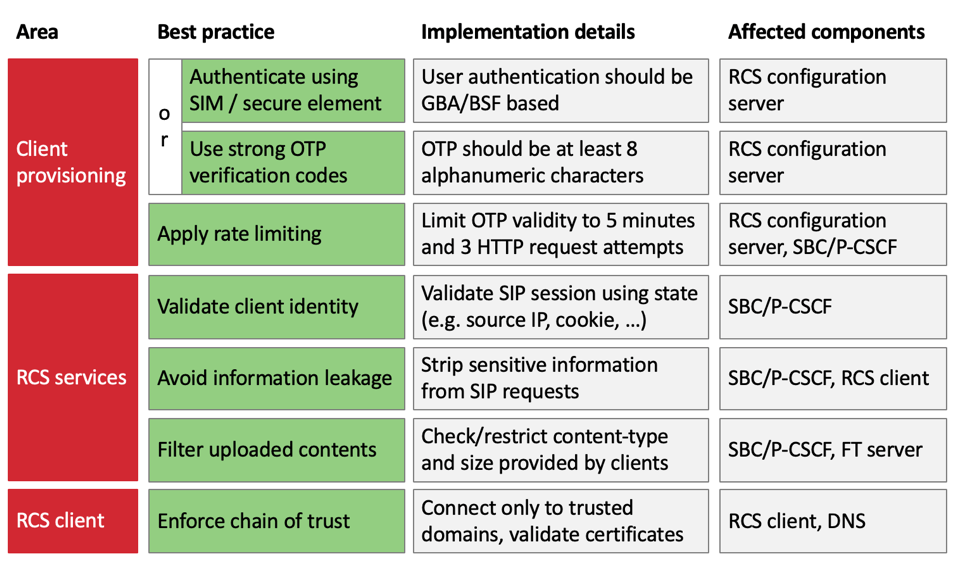

Hackers with what Nohl describes as “basic” abilities could take advantage of RCS vulnerabilities to track users, conduct fraud, impersonate users, prevent users from sending texts using a denial-of-service attack and, depending on the network, intercept texts. All of these actions, he stresses, can be prevented if network carriers implement widely used security protocols such as authenticating via the SIM card or secure chip on the phone; using “strong” one-time PIN codes that are at least eight alphanumeric characters; using rate limiting to prevent attackers from trying an infinite series of OTP combinations; validating SIP sessions, which helps connect two or more devices to each other for voice and data calls; stripping sensitive information from SIP requests; and ensuring that Internet addresses linked to by certificates are validated.

“These are not structural hacks; these are avoidable mistakes,” Nohl says. “We don’t need to change the standard. It’s just up to a few vendors to change their implementation to get it right.”

RCS’ vulnerabilities can impact devices running Google’s Android mobile operating system, which currently account for about three-fourths of the world’s smartphones. They also can impact devices running Apple’s iOS. Because iMessage is only end-to-end encrypted when a message is sent between two Apple devices, anytime an iPhone user texts with an Android user, the message is sent over whichever network protocol the carrier is using. Historically, that’s been SMS, but as RCS becomes the standard for texting, it will increasingly be RCS, Nohl says.

Carriers Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, Sprint, Telefonica, and Google and Apple, did not respond to requests for comment. Australian carrier Optus declined to comment.

“The carriers are reinventing old security problems that the industry had previously solved.”—Karsten Nohl, CEO, Security Research Labs.

Deutsche Telekom spokesperson Christian Fischer said in an emailed statement that the network is “grateful for the feedback provided by the researchers.” Fischer alleged that Deutsche Telekom has “further improved the RCS security measures already this week,” but did not respond to requests to clarify what changes the network made.

Vodafone told The Parallax in an emailed statement that it is “aware” of the research. “We will review these protections in light of the research and, if required, take any further protective measures,” Vodafone representative Otso Iho said.

The mobile network trade group GSM Association said in a statement to The Parallax that SR Labs’ research is “complementary” to “an ongoing RCS risk assessment being conducted by the GSMA’s Fraud and Security Group.”

“Preliminary consideration of the research notes that countermeasures and mitigation actions are available to protect RCS implementations against the known vulnerabilities,” GSM Association spokeswoman Claire Cranton wrote, adding that SR Labs is expected to present its findings to the GSM Association’s Fraud and Security Group next week.

The struggle to secure RCS underscores challenges in improving legacy technology, such as SMS, with open standards. Text messages carry a greater security burden than ever before: One-time use and second-factor authentication codes designed to protect our most personal online accounts, such as Google and Facebook, as well as our online banking accounts, often are sent over text message. As currently implemented, RCS leaves those messages more open to interception than its technological predecessor, and the only way to secure them depends on mobile networks taking action.

By purchasing SIM cards from multiple carriers and checking which Internet addresses they connected to that were associated with RCS communications, Nohl and his colleagues at SR Labs were able to identify five ways to hack RCS texts. Many of them start with acquiring a SIM card from the targeted network, but that’s not required in all cases.

From there, the hacker can exploit numerous misconfigurations of RCS for intercepting messages and calls. One involves a carrier sending a user a one-time code to verify their identity. Because RCS hasn’t been configured to limit how many attempts the user can make, a hacker could try a brute-force attack to crack the one-time code by trying 1 million codes in five minutes; a successful attack would let the hacker fake that user’s identity on the network.

The second attack involves sharing configuration files between the RCS-messaging app and the phone itself, which could let the hacker create an app that could take advantage of shared usernames and passwords to access texts and calls without alerting the user.

The third attack SR Labs discovered would allow a hacker with a fake mobile cell tower or Internet access point, or who is using the same legitimate tower or access point a target phone is using, to create and inject Internet traffic on to the phone.

The fourth enables the hacker to use RCS phones in denial-of-service attacks against a website by exploiting a command to automatically download a target file from the website. But this attack can also be used to track the IP address of the user, as well as take over the account of a user, if the RCS app sends back to the hacker the active-session token. The token is a small piece of software code that verifies the user and device’s identity.

The fifth attack exploits signals from the RCS communication so that the hacker can maliciously set call forwarding, fake the user’s identity on the network, redirect traffic to malicious websites and Web servers, and intercept all traffic to and from the device. Some of these attacks can be carried out with nothing more complicated than a rogue Wi-Fi hot spot, a known risk in public spaces such as coffee shops and airports.

“The carriers are reinventing old security problems that the industry had previously solved,” Nohl says. “Security responsibility in RCS has fragmented. Google controls the phone side but not the network side.”

Since our original interview in November, Nohl has uncovered another method of intercepting RCS texts and calls that exploits how the messaging app validates the certificate. SR Labs plans to include this discovery in its Black Hat Europe presentation. If the attacker can redirect the domain name server to where the certificate is pointing, “the hacker can be in the middle of the encrypted connection,” Nohl wrote in an email to The Parallax.

Because RCS is relatively new, and not as widespread as SMS, Nohl is hopeful that networks will take steps to fix their implementations of it. There haven’t been enough consumers using RCS to make it worthwhile for hackers to exploit yet, he says. But as RCS use spreads with aggressive backing from Google and carriers, he believes that RCS will become an attractive target. And because each network has a slightly different implementation, he’s concerned that RCS vulnerabilities are here to stay far longer than a stereotypical, ephemeral text.

“There’s a clear progression in mobile security from 2G to 3G to 4G to 5G that each adds sensible security standards. But RCS tears holes into otherwise secure networks. As some standards are getting more secure, this one isn’t,” Nohl says.

Disclosure: PacSec’s organizers covered part of The Parallax’s conference travel expenses.