Experts disagree on how to secure absentee votes

WASHINGTON, D.C.—If you look at the machines voters will use in many states, you might find the state of voting security disconcerting—even frightening. But if you want a real post-Halloween scare, check out how dozens of states let absentee voters cast ballots.

As a tally from the National Conference of State Legislatures reveals, four states let at least some absentees vote over the Web. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia permit some absentees to e-mail a ballot. Thirty states and D.C. accept some absentee votes via fax, which in practice often means e-mail.

And one state, West Virginia, has launched a test of a smartphone app that records votes on a small private blockchain.

READ MORE ON ELECTION HACKING

Context Conversations preview: Election security

Why current funding to secure U.S. elections ‘doesn’t cut it’ (Q&A)

There’s more to election integrity than secure voting machines

Mueller’s indictment of election hackers a cybersecurity ‘wake-up call’

Facebook’s Stamos on protecting elections from hostile hackers (Q&A)

For decade-old flaws in voting machines, no quick fix

Post-recount, experts say electronic voting remains ‘shockingly’ vulnerable

Can your vote be hacked—after you cast it?

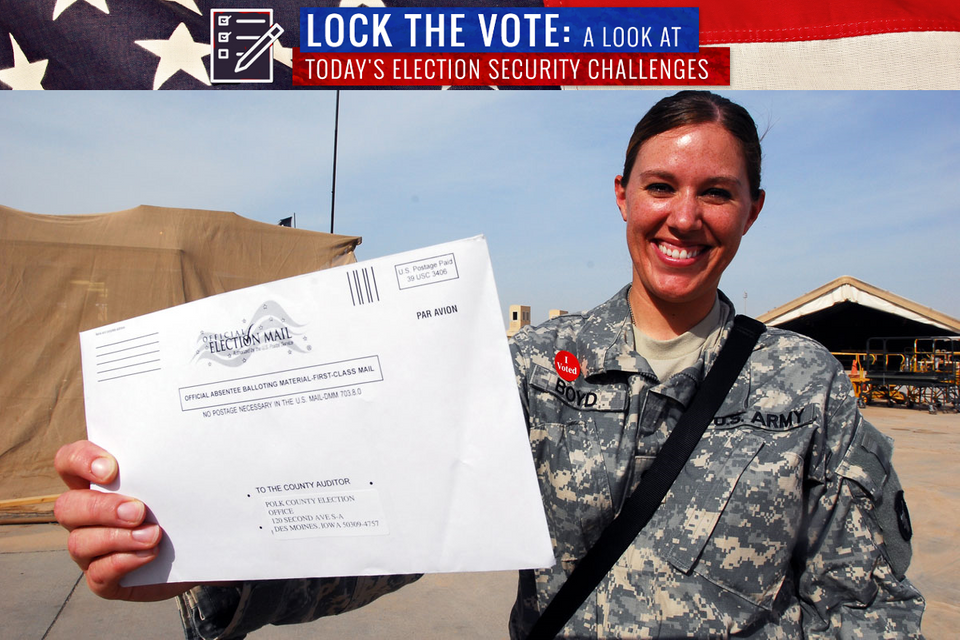

These ventures represent a response to a longstanding problem: Absentee voting can be difficult. In the 2016 general election, only 7 percent of eligible overseas voters participated, according to a survey by the Federal Voting Assistance Program. Technology promises ways to surmount these obstacles.

“We can find ways to do better at this,” says William Carter, deputy director of the Technology Policy Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, after an election security panel Tuesday morning at CSIS’s offices here. “We shouldn’t just write this off as impossible because computers are involved.”

What could possibly go wrong

A report by experts from Common Cause, the R Street Institute, the National Election Defense Coalition, and the Association for Computing Machinery’s U.S. Technology Policy Committee came to the opposite conclusion a few weeks earlier.

“It is impossible to ensure that votes cast through the Internet cannot be cast fraudulently, undetectably manipulated, or simply deleted,” authors Susan Greenhalgh (of the NEDC),

Susannah Goodman (Common Cause), Paul Rosenzweig (R Street), and Jeremy Epstein (ACM) wrote in Email and Internet Voting: The Overlooked Threat to Election Security. “States that permit online return of voted ballots should suspend the practice.”

“Voting by e-mail is probably the worst of all possible choices,” Epstein told The Parallax.

Malware on a voter’s computer may read or alter the ballot, the message may not be encrypted in transit (many still aren’t), and submitted ballot files (Alaska, for instance, accepts PDF, TIFF, or JPEG images of completed ballots) can themselves harbor malware.

“You have staff in the elections office clicking ‘open’ on all these attachments,” he says. “One of the things they teach you in Security 101 is: Don’t click on attachments.”

“It is impossible to ensure that votes cast through the Internet cannot be cast fraudulently, undetectably manipulated, or simply deleted.”—Susan Greenhalgh, National Election Defense Coalition

Voting by Web portals can reduce the attack surface slightly by using site encryption and requiring modern browsers. But those that let voters click or tap into a form don’t let voters see their choices confirmed on a paper trail, making these sites as unaccountable as direct-recording electronic (DRE) voting machines.

“It’s just like a DRE, only it’s remote over the Internet,” he says.

If, however, a voter uploads a marked-up PDF, that file could pick up malware from their computer.

And sites themselves may be hacked, as the District of Columbia learned during a 2010 test of absentee Internet voting. Researchers exploited a vulnerability to log into its voting portal, replace cast ballots, and alter the site to play the University of Michigan fight song.

The perception of these things being possible could itself be toxic, Epstein adds: “Just spreading the word that there are viruses on the loose, tampering with your vote, might be enough.”

Can you give absentees both accountability and anonymity?

Some remote-absentee systems try to stop tampering by dispensing with a secret ballot—though Epstein said not all states deploying these systems allow their voters to waive that right.

The Voatz mobile-app system West Virginia is testing with military voters overseas, for instance, runs only on a subset of phones with biometric authentication. It e-mails a copy of the completed ballot back to the voter before printing out a paper ballot that the state uses for its official count.

When Texas-based astronauts on the International Space Station vote, they’ve e-mailed a completed PDF back to Earth, where a clerk hand-copied it onto a traditional ballot.

Combining paper’s anonymity and accountability with remote voting isn’t simple. University of Florida computer science professor Juan E. Gilbert, head of the Human-Experience Research Lab there, has been working on a “televoting” system that relies on multiple webcams.

After authenticating themselves with a poll worker by stating their name and address—allowing the worker to compare that to a video recording made when they registered in person for this option—a voter would submit a completed ballot online. That would print out in the voting office, as shown on a second camera that the voter (but not the poll worker) would see in a separate window.

“Voting by e-mail is probably the worst of all possible choices.”—Jeremy Epstein, U.S. Technology Policy Committee, Association for Computing Machinery

As a further integrity check, the poll worker would draw a random number and hold it in front of the camera, and the voter would then read back the number to the poll worker.

“You get a paper ballot through telepresence that a voter can verify from a distance,” Gilbert says. “If malware changed somebody’s vote, they’ll see the difference.”

There does, indeed, have to be a better way

CSIS’s Carter said he appreciated the need to advance beyond systems that might work for online banking, where your identity sticks to each transaction.

“No one here would disagree that we need to find better ways to secure online voting,” he said of his fellow panelists. “We can find ways to do security, and we don’t need to go 100 percent back to paper.”

He suggested, for instance, that absentee-voting developers could adopt systems used in end-to-end-encrypted apps such as Signal to defeat man-in-the-middle attacks. Signal lets both parties to a call verify its encryption by reading out a series of numbers shown in each copy of the app.

Epstein, for his part, has a simpler suggestion: Let remote absentees vote by proxy, allowing a close friend or family member to cast a ballot for them.

None of these things, however, will apply to the 2018 election. At the CSIS event, panelist John Gilligan, chief executive of the Center for Internet Security, suggested that the next presidential election would be a realistic target.

“My hope is that by 2020, we have made substantial progress in that area,” he said. “There are significant benefits of using technology, and we just need to be able to figure out how to do it in a more secure way than we have.”