In post-massacre Vegas, security policies clash with privacy values

LAS VEGAS—Hackers gathered here for the annual Black Hat and DefCon conferences, among others, are sounding privacy alarms as hotel security personnel along the Las Vegas Strip demand access to their rooms.

More than two dozen hackers and security experts attending security events this week privately reported to The Parallax or publicly reported on Twitter that people identifying themselves as security personnel at the Mandalay Bay, Luxor, Caesars Palace, Flamingo, Aria, Cromwell, Tuscany, Linq, Planet Hollywood, or Mirage hotels had entered their rooms.

Except for Tuscany, which is independent, all of these hotels are owned by either Caesars Entertainment or MGM Resorts International. And of the three hotel companies, only Caesars returned a request for comment.

Richard Broome, executive vice president of communications and government relations for Caesars Entertainment, whose Caesars Palace is co-hosting DefCon this year with the Flamingo, said that following the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history last year, “periodic” hotel room checks are now standard operating procedure in Las Vegas.

On October 1, 2017, from his room at the Mandalay Bay, Stephen Paddock used semiautomatic weapons he’d outfitted with bump stocks to kill 58 people and wound at least 527 others attending a gated country music concert on the Strip below.

“We want guests to feel safe,” Broome said. “A lot of hotels have put similar policies in effect after October 1.”

As Broome explained to The Parallax during a phone call Saturday afternoon, security personnel are authorized to check on guest rooms as frequently as once a day. Security teams at Caesars, he said, are “trained” to identify themselves as security personnel when requesting hotel room entry—and, upon request for proof of identification, to reveal their hotel badges.

Further: I stated to both supervisor on the phone & security guards present that I believe in their mission of enhanced security & want to help brainstorm how to protect women traveling alone like me. They talked over me, saying my concerns were “noted” & dismissed my suggestions.

— Katie Moussouris (@k8em0) August 11, 2018

Two apparent Caesars security officers wearing hotel name tags displaying only the first names “Cynthia” and “Keith,” respectively, as well as sheriff’s style badges that looked like they came out of a Halloween costume kit, visited my room while I was writing this story. Cynthia told me that they are instructed to refer to the front desk guests who decline to allow their room to be searched.

After Cynthia and Keith declined to disclose their last names to me, I asked what they intended to do in the room. They told me that they would enter it, type a code into the room’s phone line to signal that it’s been checked, and then do a visual spot check. When I asked what they would be looking for, Cynthia replied, “WMDs—that sort of thing.”

Other conference attendees reported similar but less pleasant interactions. Katie Moussouris, CEO of Luta Security, wrote on Twitter that two hotel security personnel were “banging” on her room door and “shouted” at her. She also said the hotel’s security team supervisor “dismissed” her concerns over how the hotel was treating single, female travelers.

Google security engineer Maddie Stone tweeted that a man wearing a light-blue shirt and a walkie-talkie entered her Caesars Palace room with a key, but without knocking, while she was getting dressed.

“He left when I started screaming,” she wrote, adding that a hotel manager, upon her request, said Caesars would look into whether the man was actually an employee. (It is hardly unheard of for a person to pose as a security official or another type of authority as part of criminal action; a man was arrested on Friday in downtown Las Vegas for allegedly posing as a policeman in order to coerce women to perform sexual acts, KNTV reported.)

Stone tweeted that she left DefCon early because of the incident.

This evening, a man in a light-blue collared shirt with a walkie-talkie entered my room with a key without knocking while I was getting dressed. He left when I started screaming. @CaesarsPalace is investigating whether it was a hotel employee. @defcon has also been alerted.

— Maddie Stone (@maddiestone) August 12, 2018

Another DefCon attendee who requested anonymity said that although security staff at the Flamingo were “polite” when they checked her room, the experience was a bit unnerving.

“It was uncomfortable because when I opened the door, the one guy came right in after explaining they were there to check the room, and I didn’t get a chance to check who they were first,” she said. “And then, of course, it left me unsure if people had come in other days, when the room was empty.”

One man privately told The Parallax that a Caesars security official insisted on checking his room, even though he said he was sick with a fever.

Marc Rogers, DefCon’s head of SecOps and vice president of cybersecurity strategy for identity management company Okta, said the conference is aware of the room problems and is working with Caesars on reducing conflicts for next year.

“These changes represent the new reality that all hotels have to face in their work to keep guests safe,” he said at the conference’s closing ceremony Sunday. Caesars is “working closely with DefCon management to figure out the best way forward for next year.”

In a statement posted to Twitter on Monday, a DefCon representative added, “We expect a venue where our attendees are secure in their persons and effects, and a security policy that is codified, predictable, and verifiable. Thank you for your patience while we work this out.”

DefCon founder Jeff Moss also tweeted on Monday that although Caesars Palace had been a “great” partner for the conference, it had put DefCon “in a bad position.”

“What we were told in advance was not what happened during con,” he wrote. He did not immediately respond to questions about what DefCon was told.

The hotel has put us in a bad position by not explaining the process or scope of their new policy. What we were told in advance was not what happened during con.

That is super frustrating for all the Goons because in all other aspects the hotel has been great to work with.— The Dark Tangent (@thedarktangent) August 14, 2018

A Black Hat representative told The Parallax that the organization had not received any complaints from conference attendees.

“We’ll continue to monitor and work with our hotel partners to ensure both the safest and most pleasant experience possible for our audience,” the representative wrote in an email.

BSides Las Vegas did not return requests for comment.

Ian Carroll, a security engineer at San Francisco-based HelloSign, said a house cleaner reported him to hotel security after seeing his lock-picking equipment on the desk of his hotel room. The hotel responded by locking him out of his room.

When Carroll tried to re-enter it, two hotel security officers scolded him for leaving the equipment out, claiming that lock-picking sets are illegal in Nevada. (Lock picking is a favored pastime among hackers, and Nevada does have stricter laws than most states on possessing lock-picking kits, but it doesn’t outright ban them.)

A security researcher and Black Hat attendee who requested anonymity because of the sensitive nature of this story told The Parallax that a Mandalay Bay security employee threatened to bring “more people” to his hotel room door if he didn’t open it.

Broome said he is aware of privacy complaints from guests at Caesars but declined to elaborate. Guests who wish to file a complaint should contact the front desk and ask for the manager to contact them, he said.

“If there’s any incident, we want to know quickly,” Broome said. In the Caesars Entertainment room policy, the hotel warns guests that they can be forced to leave for refusing room checks.

“For safety and security, hotel team members will enter rooms and perform a standard wellness check, even if you have opted out of housekeeping services, posted a sign on your door, or otherwise refused team member entry. You may be asked to leave the hotel, if you do not comply with this company policy,” it reads.

In a statement released to reporters, Caesars says DefCon organizers were informed before the conference of the new policy. “The checks involve only a visual review of the bedroom, bathroom, and additional sitting area (if any) to ensure that there are no issues which require further attention. Drawers, suitcases, and other personal items are not inspected by our security officers, who are clearly identifiable to guests,” the statement said.

The Parallax has seen evidence of Caesars Palace security personnel taking more than a visual review of guest rooms—with flash photography and video-recording equipment. We reviewed a video provided by Jason Painter, president of Queercon, showing two Caesars Palace security personnel entering rooms rented by the LGBTQ+ hacker group. In the video, the guards move throughout the rooms, using what appears to be a smartphone to record video and take flash photography of the organization’s possessions, and joking about posting the the photos and video to Snapchat.

Representatives of Caesars Entertainment did not immediately respond to questions about how Caesars’ room-check policy relates to documenting guest rooms.

Las Vegas hotels ostensibly established room-checking policies to reduce the chances of guests amassing weapons in their rooms, as Paddock successfully did in October, despite reportedly interacting with Mandalay Bay room service and housekeeping staff more than 10 times over a period of three days.

Like airport security practices established in the wake of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, such as removing shoes, disposing of liquid containers larger than 3.4 ounces, and having passengers submit to full-body scans at security check points, it isn’t clear how effective room checks will be in preventing another massacre on the Strip.

Computer Security as a profession has been through extensive, painful reckonings on effectively communicating trust signals to the public. It’s interesting how we react to authority that doesn’t feel a need to up-front prove its authentic provenance. Deep cultural fissure here. https://t.co/zxNuNctijd

— SwiftOnSecurity (@SwiftOnSecurity) August 12, 2018

The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Confrontations over privacy between hotel security personnel, and security experts attending Black Hat and DefCon, reflect struggles security experts face in getting the software industry to take responsibility for security vulnerabilities and disclosure.

In two posts this weekend, the popular anonymous Twitter account SwiftonSecurity highlighted the “deep cultural fissure” between how security professionals act in protecting clients, and how they expect to be treated by others—especially when it comes to transparency over privacy policies and gaining trust.

“Computer security as a profession has been through extensive, painful reckonings on effectively communicating trust signals to the public. It’s interesting how we react to authority that doesn’t feel a need to up-front prove its authentic provenance,” SwiftonSecurity tweeted in response to my call for personal anecdotes on the room search policy on Saturday.

“If your users are upset by security measures forced upon them, which they do not understand, nor are they educated about effectively before/during/after, and end up with the user feeling violated—that’s often 95 percent remediable through design changes in the interaction,” Swift added.

Some DefCon attendees are claiming on Twitter that they will refuse to attend the conference next year, if it returns to Las Vegas. Of the more than 1,650 votes in response to an informal poll started by Twitter user @notdan, a security researcher at a tech company in the San Francisco Bay Area who requested anonymity, 35 percent said they would not return to DefCon over room privacy concerns.

“Over the next few days, if I read that all hotels are adopting this, [I] will definitely not be back. Vegas is hacker/privacy hostile territory at that point,” he wrote in a message to The Parallax.

Are you planning on avoiding DEFCON next year because of the privacy invasions into your room? Please RT for reach on this one

— uɐpʇou@ ✸ (@notdan) August 11, 2018

In a message to The Parallax, Moussouris emphasized a similar concern: that hotel room privacy is of paramount importance, especially for female travelers. “No matter whether DefCon moves or stays put, all hotels should have basic protocols for allowing any guest to easily authenticate a supposed hotel employee,” she wrote.

The Las Vegas hotels are doing the right thing to protect their guests, argues a retired regional manager for one of the world’s largest hotel chains, who requested anonymity because he’s still involved in the hotel industry.

Before the massacre, if hotel staff suspected that something suspicious was occurring in a room, hotel policy was to send a front-desk staffer and security personnel to investigate, he said during a phone call. And if police wanted access to a room, they would have to show up with a subpoena.

Las Vegas hotels’ security protocol update “is a precursor for where other hotels will go,” he said. “The chains will set up rules, as long as it’s not in violation of federal law.”

Hotels, however, should be much more transparent about their policy updates, he said. “There needs to be much more information” about them. “They need to say [the] new policy allows [them] to enter your room—[and] maybe make it visible on the TV welcome message.”

Broome said in a text message that Caesars’ new room-checking policy is “enhancing the security” of its hotels while helping its staff identify guest issues that require police intervention or medical assistance.

Not everyone thinks that the hotels are taking effective measures to protect their guests. More aggressive room searches likely have little to do with keeping guests safe, according a prominent civil-rights attorney, who noted that in July, Mandalay Bay owner MGM sued more than 2,500 of the shooting victims in an attempt to dismiss claims that it is liable for deaths or injuries related to Paddock’s actions.

“Their corporate lawyers told them to avoid a negligence suit by searching rooms so that exactly what the concert shooter did (stockpile weapons in his room) won’t happen again,” the attorney, who requested to remain anonymous, wrote in a message to The Parallax. “The result is, we are always preventing the last attack. But we aren’t good at predicting future attacks. Efforts to do so are usually hapless and invasive.”

Caesars changed out my ‘do not disturb’ sign. New one adds fine-print language about reserving the right to enter for “any…purpose.” pic.twitter.com/G91FSEEJlP

— Kurt Opsahl (@kurtopsahl) August 12, 2018

And Kurt Opsahl, a senior staff attorney for the digital-rights group the Electronic Frontier Foundation, tweeted that Caesars swapped his “Do Not Disturb” sign for one with fine print “reserving the right to enter” the room.

Opsahl brought up a U.S. Supreme Court case and two 9th Circuit Court of Appeals cases to shed light on relevant legal issues: when it’s appropriate for hotel staff to enter a hotel (United States v. Jeffers); when guests have a right to privacy in hotel rooms (Eng Fung Jem vs. United States); and what happens when police accompany hotel staff for a room search (United States vs. Reed).

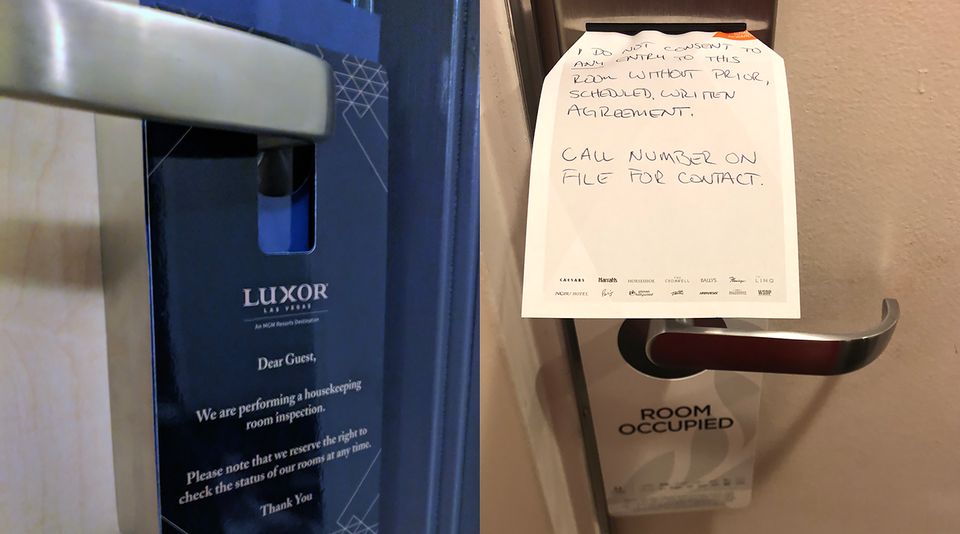

At least one security conference attendee decided to apply his hacker ethos to room security. Beau Woods, a cybersafety fellow at the Atlantic Council policy think tank, set up a room surveillance system of his own using an old smartphone and a motion detection video surveillance app that texts him when activated.

He also stuck a note in the door lock that reads, “I do not consent to any entry to this room without prior, scheduled, written agreement. Call number on file for contact.”

A jerry-rigged surveillance camera isn’t likely to be an option for most travelers. But by the end of the conference, Woods said his room had not been entered by hotel staff.

Update, August 13 at 11:55 a.m. PST: Added mention of Planet Hollywood, a Caesars Entertainment hotel.

Update, August 13 at 2:12 p.m. PST: Added a comment from DefCon.

Update, August 13 at 10:45 p.m. PST: Added a comment from DefCon founder Jeff Moss.

Update, August 14 at 1:54 p.m. PST: Added mention of Caesars security personnel using photography and video-recording of guest belongings in hotel rooms.

Update, August 16 at 1:05 p.m. PST: Added description of Queercon video footage of Caesars Palace personnel in hotel rooms.