Why tech still can’t explain its own requests for your data

Once again, a tech company has found itself offering the stereotypical excuse of a soap opera spouse caught in bed with the wrong person: “This isn’t what it looks like!”

This time around, the offender is Facebook, after The New York Times reported in mid-December that a variety of data-sharing deals had exposed Facebook users’ messages to such third parties as Netflix and Spotify.

Facebook’s response—after an initial fumble that ignored key points of the Times’ story—was to fall back on the finer points of messaging architecture.

“For the messaging partners mentioned above, we worked with them to build messaging integrations into their apps so people could send messages to their Facebook friends,” wrote Ime Archibong, Facebook’s vice president of product partnerships. “These partnerships were agreed via extensive negotiations and documentation, detailing how the third party would use the API, and what data they could and couldn’t access.”

If you’re trying to explain a standard practice of setting up a mail client to connect to another company’s mail server, this type of response would be appropriate. But to a nontechnical audience, fine-grained defenses like this evoke the old political line, “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.”

We’ve seen this story before

Facebook’s original mistake in this messaging mess was to act as if everybody who clicked or tapped on “OK” or “I agree” once did so with a complete understanding of where their messages were moving.

If you know what mail protocols like POP and IMAP do—or knew of Facebook’s 2010 plans to turn its messaging system into a standards-compliant email replacement—that’s a reasonable expectation. Reading or writing your mail someplace outside of the company running the service necessarily involves another company holding those bits for a while.

Other aspects of the Times’ reporting hold up, and have yet to get the same detailed pushback from Facebook.

But acting as if you expect laypeople to recognize canonical notions of information access and then think in the appropriate flowcharts—and, moreover, acting shocked when people don’t grok those technical details—is usually a mistake.

In 2009, Facebook endured a storm of criticism after it made the avoidable error of letting its lawyers write a new terms-of-service document that appeared to impose sweeping claims of ownership—as in, “an irrevocable, perpetual, nonexclusive, transferable, fully paid, worldwide license”—on the things Facebook users shared on the network.

Protestations of innocence left many users unpersuaded, because why would they be expected to understand intellectual-property legalese meant to immunize a company in the broadest sense imaginable?

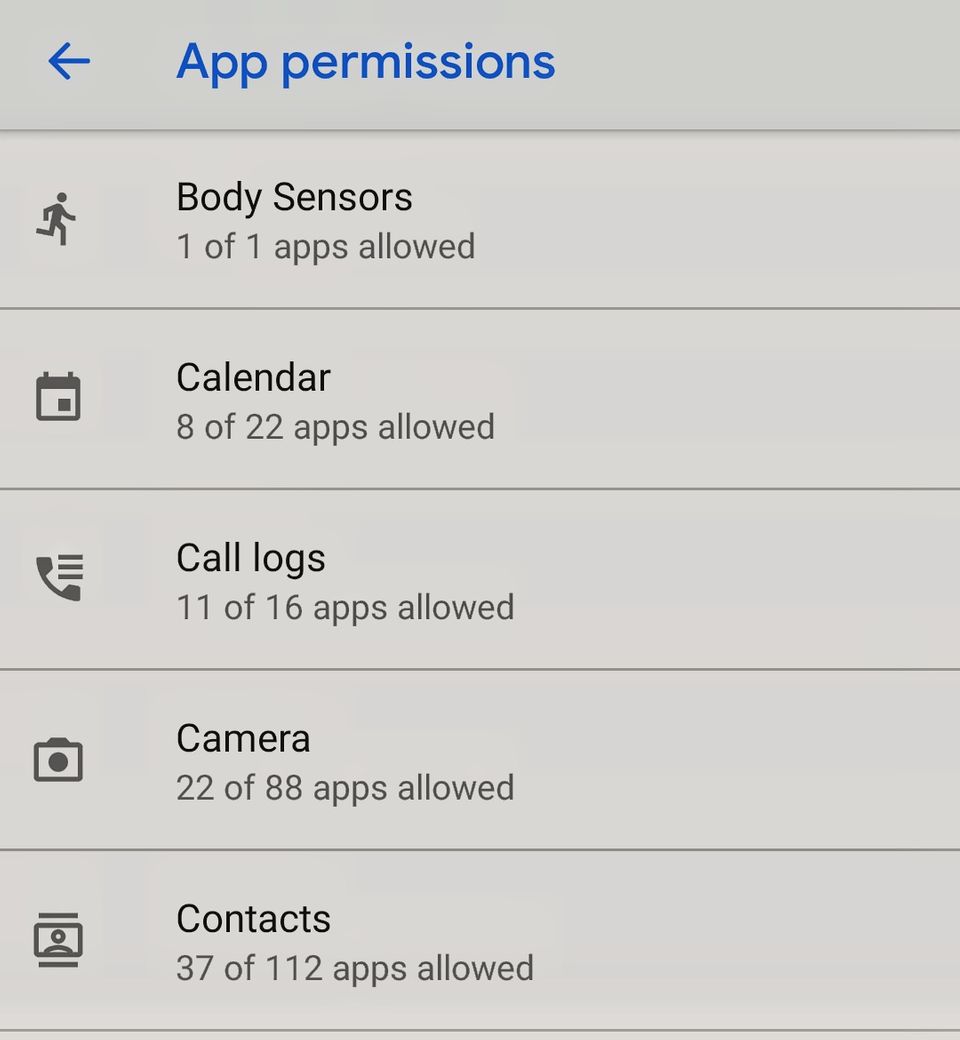

The same dynamic has played out in arguments over the data permissions some mobile apps throw up. In 2014, security researcher Joe Giron took a close look at the permissions Uber’s Android app listed for access to such data sources as user contacts and cameras, and summed up his reactions as, “Why the hell is this here?”

In context—as Uber now explains on its site—these requests make sense. Sharing your ETA is quicker, if you can type in somebody’s name, and using your camera to take a selfie for your account profile or entering credit card data is faster when done right in the app.

But again, why would you expect a reasonably paranoid person to read such an open-ended request as the product of a binary, yes-or-no permissions regime?

When in doubt, leave it out

Flattening storage costs and the importance of keeping a startup open to a pivot to a new business model have invited companies to keep as much data as possible and figure out how to monetize it later.

And other companies have been as loose or looser with your data than Uber and Facebook. Lyft’s Android app, for example, wants access not to your contacts list but also to your calendar.

And while Apple’s iOS has a good reputation for privacy, it still doesn’t impose a time-out on AirDrop anonymous file sharing, with the gross but unsurprising result of people getting “cyber-flashed” on trains and planes.

To privacy-focused consumers, the rare app that exhibits a restrained appetite for data is not just welcome, but an example others should follow.

Consider, for example, Eventbrite’s Android app, which doesn’t ask for calendar or contacts access but still lets you add an event to your calendar or mail it to a friend using standard Android sharing features.

Or look at the Twitter apps that request only read access to your account info, because that’s all they need to do their work (if your account shows others asking for write access that you don’t approve of, remove them now).

Data minimization is an underrated part of Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, but it shouldn’t be a hobby reserved for the eastern side of the Atlantic. Not collecting user data means never having to apologize for losing it.

Your sales pitch should be your privacy policy

In some cases, either basic app functionality or commercial demands will require granting an app more than one-time, just-take-a-peek access to your data.

That’s when a crassly capitalistic explanation of an app’s curiosity would be appropriate: Augment the text lawyers wrote for the privacy policy or permissions request with what went into the pitch for advertisers or funders, so people can know how this is supposed to make money.

For example, a ride-hailing app’s request for camera access might include the marketing rationale for it: “We saw too many people abandon their account setup when we made them type in their credit card number.” It could then add a reminder that in Android and iOS, you can revoke that permission after taking a picture of a card.

And a social network’s request for your contacts could come with a note explaining how it expects this to fuel adoption: “Our investors have told us they want to see this number keep climbing.”

A proposal posted December 13 by the Center for Democracy & Technology offers a new wrinkle: requiring companies to post their privacy policies in a machine-readable format. That would let a hypothetical privacy guardian service tell you on its own whether it’s safe to use a third-party app.

But a check at sites I’d complimented in early 2013 for having plain-English privacy rules revealed that most had reverted to industry-standard privacy legalese that humans, let alone computers, might struggle to read.

Sticking with that habit may be the easiest path forward. But when the next privacy scare hits, that will leave tech companies hoping they can skate by with the half-hearted defense of Uber that Giron posted after taking a second look at its app: “I found the capabilities for Uber to spy. It doesn’t mean Uber is spying. The app can, but it doesn’t.”